Many individuals can empathize with the discomfort caused by the sound of nails scraping on a chalkboard. However, those who experience misophonia often respond with equal intensity to sounds such as slurping, snoring, breathing, and chewing.

According to a study conducted in 2023, misophonia may be more widespread than earlier estimates indicate. European research has highlighted that this condition shares genetic links with anxiety, depression, and PTSD.

A team led by psychiatrist Dirk Smit from the University of Amsterdam conducted a comprehensive analysis of genetic data sourced from the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, UK Biobank, and 23andMe. They discovered that individuals identifying as having misophonia were significantly more likely to carry genes linked to psychiatric conditions and tinnitus.

Research indicates that patients with tinnitus—characterized by persistent ringing in the ears—are also at a higher risk of experiencing symptoms related to anxiety and depression.

“There is a genetic overlap with PTSD,” Smit stated in an interview with Eric W. Dolan at PsyPost. “This suggests that genetic predispositions to PTSD may also heighten the risk for misophonia. This could indicate a shared neurobiological pathway affecting both conditions, implying that treatments for PTSD might also benefit those with misophonia.”

It’s important to note that while misophonia may share some genetic risk factors with these disorders, they do not necessarily operate on the same mechanisms.

Earlier findings have illustrated that individuals experiencing misophonia are more inclined to internalize their distress. The 2023 study by Smit and his team corroborated this, revealing significant connections with personality traits such as anxiety, guilt, loneliness, and neuroticism.

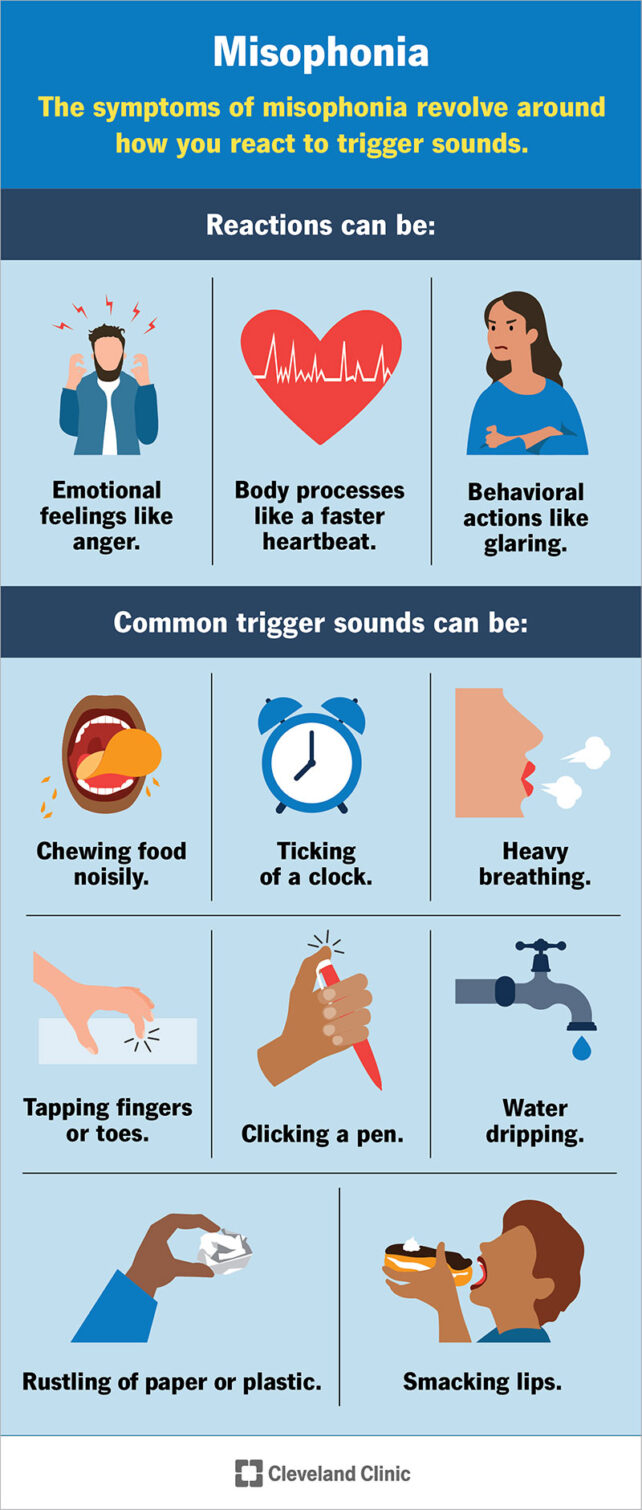

Reactions to triggering sounds can vary widely, from mild irritation and anger to profound distress that disrupts daily activities.

“It has been suggested that misophonia may stem more from feelings of guilt regarding the anger and irritation caused by these triggers, rather than the overt expressions of anger themselves,” the researchers noted in their publication.

Interestingly, individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are less likely to develop misophonia, which is surprising given that those with ASD typically exhibit lower tolerance to auditory stimuli.

“Our findings indicate that misophonia and ASD are largely independent conditions concerning genetic variation,” the researchers stated in their paper. “This suggests that other forms of misophonia might exist, primarily influenced by the conditioning of negative emotions such as anger in relation to particular trigger sounds, shaped by personality traits.”

Smit and his collaborators caution that their findings primarily reflect a European demographic, and the same genetic links may not apply to other populations. Additionally, the data on misophonia was self-reported, which could introduce biases into the results.

Nonetheless, their study provides valuable insights that could guide future research in unraveling the biological underpinnings of misophonia.

This research appeared in Frontiers in Neuroscience.

A previous version of this article was published in October 2024.