Imagine this classic scenario: you find yourself at the base of a hill and your goal is to reach the summit. Should you tackle the steepest route or take a switched-back path with a gentler slope? The answer varies based on the situation. If there’s a designated trail, for instance, it’s advisable to follow the established switchbacks. A broader perspective, however, involves understanding the physics at play.

This is precisely the goal of a recent study published in the journal Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, conducted by a team led by David Looney and Adam Potter from the U.S. Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine. Earlier research indicated that for runners, the concept of “steeper is cheaper” prevailed—that is, it requires less energy to ascend steeper slopes. The question remained whether this principle also applies to walkers and backpackers, and whether external temperatures influence this dynamic.

Optimal Slopes for Trail Runners

Firstly, let’s revisit trail-running research. In 2016, a team from the University of Colorado sought to investigate the growing trend of vertical kilometer races, which involve a total elevation gain of 1,000 meters (3,281 feet). Each course varies in difficulty: a steeper slope shortens the distance but adds challenge, while a gentler incline makes the run easier but offers greater distance. What’s the ideal compromise for average finish times?

The Colorado researchers constructed the world’s steepest treadmill (watch the video here), capable of achieving a 45-degree slope. For perspective, a black diamond ski run measures around 25 degrees, while most gym treadmills are limited to 9 degrees. They had to cover the treadmill with sandpaper for traction, and even then, runners struggled to maintain balance beyond 40 degrees.

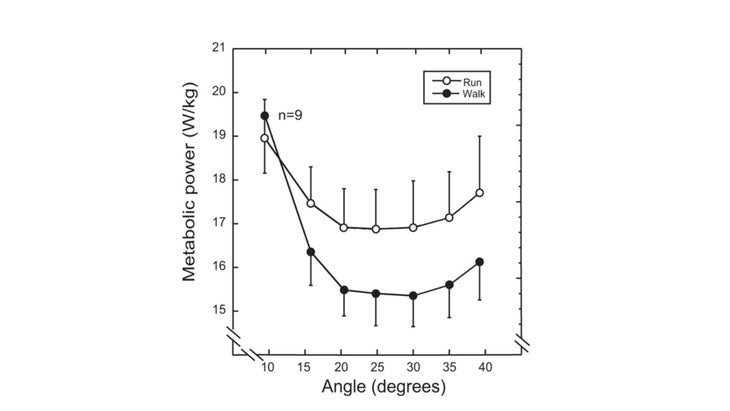

During the experiment, runners were tested on various slopes, with the treadmill speed adjusted to ensure a consistent elevation gain, equivalent to a vertical kilometer achieved in a commendable 48 minutes (the world record stands at slightly under 30 minutes). The findings illustrated the metabolic rates (indicating calorie burn) for both walking (black circles) and running (white circles):

At milder slopes, such as 10 degrees, climbing requires significant energy due to the treadmill’s rapid speed necessary to gain elevation. However, as slopes become steeper, the energy expenditure decreases, supporting the idea that steeper is indeed cheaper—up to a certain point. Beyond around 30 degrees, calorie burn begins to rise again, likely due to the increased difficulty in climbing efficiently. This indicates that an ideal range lies between 20 and 30 degrees, which aligns with the average slopes found in fast vertical kilometer races.

It’s worth noting that walking generally expends fewer calories than running at steeper angles, a realization many trail runners come to understand firsthand. However, this doesn’t imply that walking uphill should be the exclusive method, as I discussed in this article on the walking versus running dilemma in trail running.)

Best Slopes for Hikers

Reaching a kilometer in 48 minutes is quite rapid—roughly equivalent to sprinting a 10-kilometer run—making the Colorado findings less relevant for backpackers or military personnel. Looney and his team decided to conduct similar experiments at slower climbing speeds. The Colorado study employed a rate of 21 vertical meters per minute, whereas Looney’s study focused on four climbing rates ranging from 1.9 to 7.8 meters per minute, providing a more realistic representation for hikers.

Overall, findings mirrored those of the running studies: steeper slopes consistently resulted in lower calorie consumption. However, similar to the running data, there is likely a threshold where excessive steepness may hinder efficiency. In this study, the steepest slope tested was only around 13 degrees, and throughout this range, a steeper incline continued to be beneficial.

Looney’s study introduced another factor: as the military is focusing more on Arctic operations, they ran the same protocols at three distinct temperatures: 32, 50, and 68 degrees Fahrenheit. While the two warmer temperatures yielded comparable results, the data at 32 degrees displayed slight variations.

At lower vertical climbing speeds, calorie burn was elevated at 32 degrees, as participants expended additional energy to stay warm through shivering and activating their brown fat. Conversely, at faster climbing rates, calorie burn remained largely consistent across temperatures, likely because participants were exerting enough effort to maintain warmth even in cooler conditions. In essence, climbing more intensely in cold weather can sometimes be more efficient since it mitigates energy loss from staying warm. On the other hand, steeper inclines in hot conditions may risk overheating.

Key Takeaways

When interpreting these findings, it’s crucial to remember that comparisons are made based on a fixed climbing rate. If you aim to reach the top of a hill “within a certain timeframe“, choosing a steeper path will typically conserve more energy. However, if time is not a constraint, opting for a gentler slope may yield a more comfortable ascent.

For most individuals, though, time is often a limitation. Even if not racing vertical kilometers, we usually strive to reach our destination before nightfall. Thus, when faced with two route options, keep this in mind: if one path is twice as steep as the other, you would need to ascend the gentler route at double the speed to summit in the same amount of time. Surprisingly, data suggests that under most conditions, a steeper route is easier than traversing a more gradual one at a faster pace.

For additional insights from Sweat Science, connect with me on Threads and Facebook, sign up for the email newsletter, and explore my upcoming book The Explorer’s Gene: Why We Seek Big Challenges, New Flavors, and the Blank Spots on the Map.