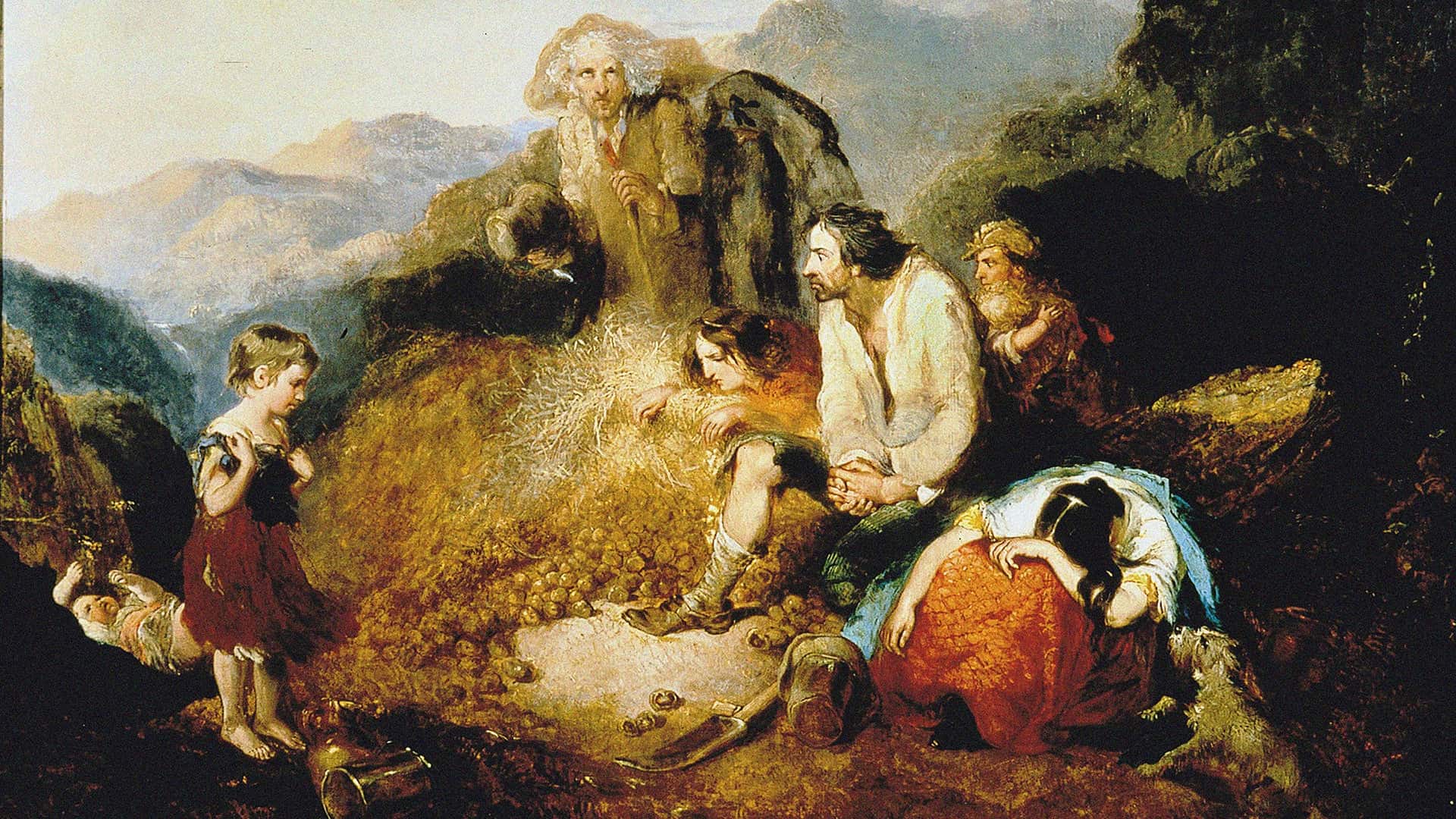

During the mid-1800s, a minuscule pathogen wreaked havoc across Ireland, leading to immense tragedy and suffering. This potato blight, caused by the fungus-like organism Phytophthora infestans, resulted in the deaths of over a million people and prompted millions more to flee. For over a century, scientists have debated the origins of this lethal microorganism. Did it emerge from the rugged Andes, where potatoes were first cultivated, or from the highlands of Mexico, rich in similar pathogens?

Recent research now suggests a resolution to this historical mystery. In one of the most extensive genetic studies conducted, researchers have traced the roots of the potato blight back to the Andean region. These findings not only resolve a long-standing scientific debate but also unveil a complicated history of evolution, migration, and hybridization that has influenced the development of one of the world’s most notorious plant diseases.

The Journey of a Pathogen

Even today, Phytophthora infestans continues to devastate potato and tomato crops globally, resulting in billions of dollars in agricultural losses annually. Understanding its origins could be essential for scientists aiming to anticipate and manage future outbreaks.

The discussion surrounding its birthplace has been intense. Some researchers advocated for a Mexican origin based on evidence of the pathogen’s sexual reproduction in that area. In contrast, others leaned toward an Andean origin based on genetic data. The new study, spearheaded by Allison Coomber and Jean Ristaino from North Carolina State University, presents a wealth of genomic insights.

The research team analyzed complete genome sequences from P. infestans and six closely related species, including P. andina and P. betacei from South America, as well as P. mirabilis and P. ipomoeae, which are native to Mexico. Historic samples of P. infestans collected during the Irish Potato Famine were also included in the study.

The findings were definitive. The Mexican species P. mirabilis and P. ipomoeae formed separate genetic clusters from P. infestans. In contrast, P. infestans showed close genetic ties to the Andean species P. andina and P. betacei, indicating a closer relationship akin to that of siblings rather than distant relatives.

“This is how scientific inquiry advances,” stated Jean Ristaino, a co-author of the study and professor at North Carolina State University. “You start with a hypothesis, face scrutiny, conduct tests, and present your findings. Over time, the evidence increasingly supports the Andean origin, as DNA analysis reveals the truth.”

Historical documentation supports the Andes as the origin. “When the blight first affected Europe and the U.S. in 1845, there were immediate attempts to uncover its source,” Ristaino noted in an interview with The Guardian. “Reports indicated that the disease had previously occurred among the indigenous Andean populations growing potatoes.”

The Andean Crucible

Genetic analysis indicates that the common ancestor of P. infestans and its Andean relatives diverged from the Mexican species roughly 5,000 years ago. Subsequently, P. infestans dispersed from the Andes to various parts of the globe, including Mexico and Europe, facilitated by expanding trade networks and globalization.

The research also uncovered surprising levels of gene exchange among P. infestans and its Andean relatives. Migration rates were significantly higher between these species than with the Mexican ones, suggesting that the Andean region is not only the birthplace of P. infestans but also an area of active evolution.

One of the most fascinating conclusions drawn from the study was the indistinct genetic boundaries between P. infestans, P. andina, and P. betacei. These Andean species have such close genetic relationships that hybridization frequently occurs, resulting in a variety of new genetic combinations. This interaction resembles a melting pot where various microbial species exchange genetic material, potentially leading to new strains with different virulence characteristics – some of which might evade plant defenses.

Grasping the origins of the destructive potato blight has significant practical implications for management strategies, as it remains a global agricultural threat.

Potato blight still poses significant challenges worldwide. In Europe, strains resistant to fungicides have emerged, compelling farmers to search for new treatment options. Innovative breeding techniques and gene-editing methods hold promise for long-term solutions.

“Understanding where a pathogen originates is critical for finding resistance,” Ristaino emphasized. “Long-term management strategies for the disease should focus on enhancing host resistance in the Andes.”

As the world faces ongoing struggles with food security and climate challenges, research like this is more vital than ever.

The study’s findings were published in the journal PLOS ONE.