A measles outbreak is currently ongoing in West Texas and New Mexico, raising concerns about the potential severity of the situation.

It’s crucial to understand that measles is one of the most transmissible diseases globally—more contagious than Ebola, smallpox, or nearly any other infectious illness.

Prior to the widespread adoption of vaccinations in the U.S., measles was a common childhood illness, resulting in the deaths of 400 to 500 children annually.

However, the effectiveness of the vaccine in preventing outbreaks diminishes significantly as vaccination rates drop. We consulted experts to clarify how reduced vaccination coverage can influence the spread of measles and its implications in the current outbreak.

Understanding Measles Transmission

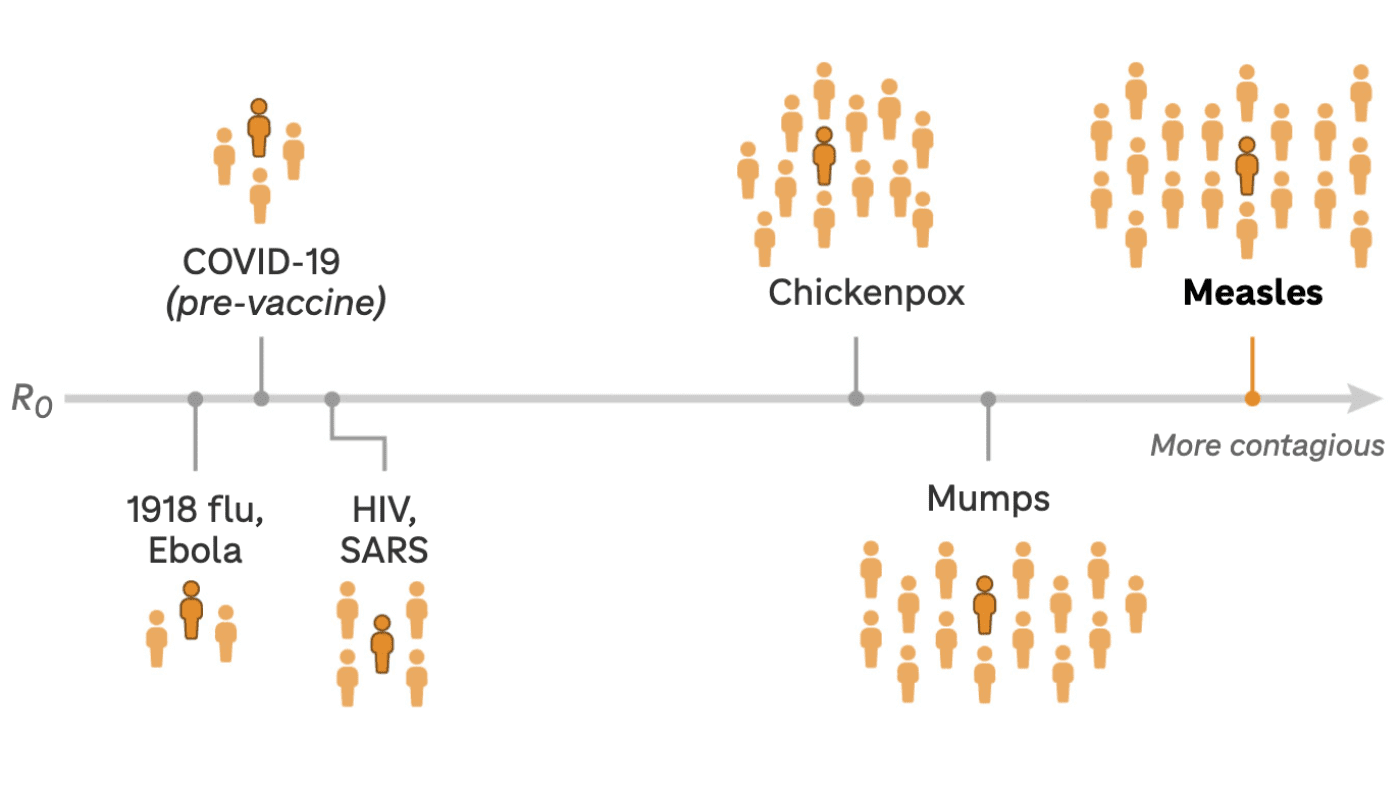

To comprehend how measles spreads, it’s vital to grasp the concept of the basic reproduction number, or R naught. This figure indicates the average number of individuals that one infected person can transmit the disease to.

For measles, R naught typically ranges from 12 to 18, meaning an infected individual can spread it to as many as 18 other people on average. In comparison, Ebola has an R naught of just 2.

However, R naught is a theoretical figure. “It’s not an immutable constant,” points out Justin Lessler, an epidemiologist at the University of North Carolina Gillings School of Global Public Health.

This number assumes that no individuals have immunity to the disease; hence, “naught” signifies zero immunity. It’s a practical metric for comparing the transmission potential of various infections. However, numerous factors can influence how measles spreads in real-world scenarios.

This leads us to the concept of the effective reproduction number, which reflects how many people a person with measles can infect in a particular population at a specific moment. This number fluctuates as more people achieve immunity through infection or vaccination.

Behavioral factors also play a role. Are infected individuals self-isolating? Are unvaccinated groups congregating together? Such environments provide an opportunity for the virus to thrive, says Lessler.

The most effective method to prevent transmission remains vaccination.

The following illustration demonstrates how significantly lower vaccination rates can impact the spread of measles among a hypothetical group of kindergartners who gather daily in a classroom.

If the reproduction number of a disease is below 1, the infection rate will be slow, and outbreaks will eventually cease, as each infected person transmits the illness to fewer than one other person on average.

Conversely, high reproduction numbers can lead to rapid case growth. For instance, if a measles outbreak has an effective reproduction number of 3, it may initially seem manageable. However, those three individuals can go on to infect three more people each, leading to exponential growth in cases.

Interestingly, the original strain of the virus that causes COVID had an effective reproduction number of around 3, and we witnessed the consequences, according to Matt Ferrari, a biology professor and director of the Center for Infectious Disease Dynamics at Penn State University.

“It’s plausible that measles could spread as quickly as [pre-vaccine] SARS-CoV-2 in certain populations, particularly in schools where vaccination rates fluctuate between 80-85%,” Ferrari notes.

At-Risk Areas in Texas

In Gaines County, the center of the current outbreak in Texas, the kindergarten vaccination rate for measles is just below 82%. This figure falls significantly short of the 95% threshold needed to effectively safeguard communities from outbreaks, as identified by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Nationally, measles vaccination rates have been declining over the years and currently stand at 92.7%. In certain areas, kindergarten vaccination rates are substantially lower, creating pockets where measles can spread.

Approximately half of Texas counties have kindergarten vaccination rates below the crucial 95% threshold. In Foard County, for instance, the vaccination rate is nearly 67%. In such a classroom environment, it’s estimated that one infected child could spread measles to five unvaccinated peers on average.

If you examine vaccination rates at the school level, the figures can be even more alarming. One private school in Fort Worth reported a kindergarten vaccination rate of only 14%. While it’s uncertain whether this outbreak will reach these areas, if it did, they would be extremely vulnerable.

Lessler emphasizes that various factors will influence how far the outbreak spreads and its overall impact. These factors include the rate of vaccination uptake in response to the situation, the quarantine of suspected cases, and the effectiveness of contact tracing to prevent further infections.

This aspect is vital as a person infected with measles remains contagious from four days before the rash appears and continues to be so for four days afterward, states Dr. Carla Garcia Carreno, a pediatric infectious disease expert at Children’s Medical Center Plano in Texas.

“You may transmit the virus even before being aware you have measles,” Carreno explains. The measles virus can remain airborne for up to two hours after an infected person has left the room, complicating control efforts.

According to Lessler, in communities where under-vaccinated individuals are congregated—like the tightly-knit rural area at the center of the current outbreak—measles can initiate significant outbreaks. However, he believes that the wider population’s higher vaccination and immunity levels will ultimately help control the situation.

“It’s unlikely that we will experience thousands or tens of thousands of cases from this outbreak, thanks to the protective barrier offered by vaccinations,” Lessler reassures. “However, if vaccination rates continue to decline amid growing anti-vaccine sentiment, we could witness a return to widespread measles outbreaks in the next five to ten years.”