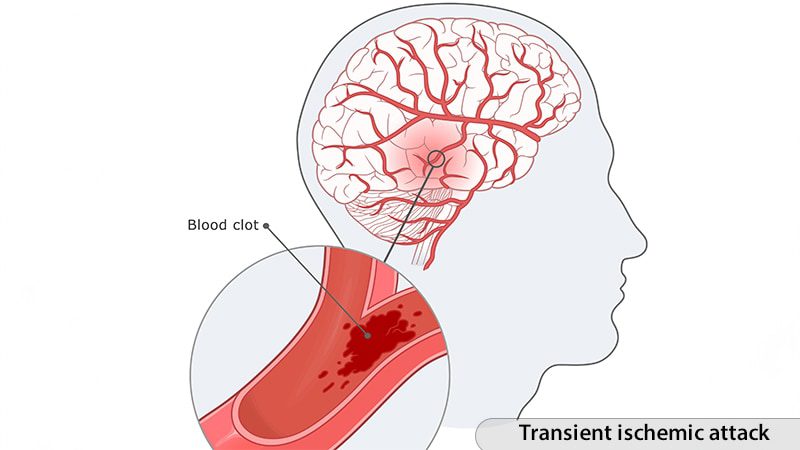

Recent research suggests that individuals experiencing their first transient ischemic attack (TIA) may face long-term cognitive decline comparable to that of stroke survivors. This finding challenges longstanding assumptions about the neurological effects of TIAs, according to a study led by Victor A. Del Bene, PhD, an assistant professor at The University of Alabama at Birmingham Heersink School of Medicine.

The research team recommends that healthcare practitioners conduct cognitive evaluations for patients who have experienced their first TIA. In the February 10 issue of JAMA Neurology, Del Bene and colleagues noted, “While stroke is known to increase the likelihood of cognitive decline and dementia, the association between TIA and vascular cognitive impairment remains less understood.”

To investigate this connection, the researchers performed a secondary analysis of data from 16,203 participants in the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke study. This diverse group included 356 individuals with a first-time TIA, 965 individuals with a first-time stroke, and 14,882 asymptomatic controls.

Cognitive abilities were evaluated biennially through various assessments, including verbal fluency and memory tests such as the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease Word List Learning, Word List Delayed Recall, letter fluency, and animal naming tasks.

The primary metric of interest was a standardized cognitive composite score, alongside secondary outcomes that assessed specific areas of cognitive performance.

To differentiate TIA’s effects from preexisting cognitive issues or other vascular risk factors, the team applied segmented regression models. This approach allowed them to monitor cognitive changes before and after the cerebrovascular event while controlling for demographics, education, and factors like hypertension, diabetes, and atrial fibrillation.

Prior to their TIA, participants’ cognitive trends resembled those of asymptomatic controls. However, following a TIA, there was a marked acceleration in cognitive decline. The annual cognitive decline for TIA patients was measured at -0.05 SDs per year compared to -0.02 SDs per year for controls (P = .02). Remarkably, the decrease noted in the TIA group was not significantly different from that within stroke survivors, who demonstrated a -0.04 decline per year (P = .43).

Memory recall, both immediate and delayed, significantly contributed to the cognitive decline observed in TIA patients, while verbal fluency showed less impact. This implies that TIAs may target memory-associated brain regions, although precise mechanisms remain ambiguous.

New Insights Challenge Established Views on TIAs

In an accompanying editorial, neurologists Eric E. Smith, MD, MPH, from the University of Calgary, and Babak B. Navi, MD, from Weill Cornell Medicine, argue that these results undermine the traditional perspective that TIAs are benign occurrences with no lasting repercussions.

“TIAs should not be considered harmless; instead, they may be warning signs of ongoing cognitive decline,” they assert.

The editorial highlights that the new research effectively addresses many shortcomings of earlier studies by utilizing a large, varied participant pool, extensive follow-up periods, and thorough evaluations of TIA and stroke cases.

Regardless, the specific mechanisms that lead to cognitive decline following a TIA remain poorly understood. Smith and Navi speculate that factors like beta-amyloid and tau pathology, disrupted gamma-aminobutyric acid transmission, or compromised blood-brain barrier may contribute to neuroinflammation.

They noted a parallel phenomenon with accelerated cognitive decline after systemic vascular incidents, such as myocardial infarction, suggesting potential roles of systemic inflammation and post-event emotional responses.

These findings carry significant implications for clinicians treating TIA patients, as emphasized by Smith and Navi. They recommend that TIAs not merely be viewed as isolated incidents but recognized as indicators of potential long-term neurological impairment.

“Healthcare providers, including stroke-prevention specialists and primary care practitioners, should engage with TIA patients and their families about any cognitive symptoms and be prepared to conduct cognitive screenings,” they recommend. “TIAs should be regarded as not only markers for adverse vascular events but also as indicators of cognitive decline risk.”

The need for further exploration into the links between TIA and cognitive impairment is critical, according to Smith and Navi. Areas for future research could include examining neuroinflammatory factors, using advanced imaging to detect subtle brain changes, and investigating interactions with neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s. Gaining insights into these mechanisms may help in developing future therapeutic approaches to mitigate cognitive decline post-TIA.

The research received funding from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the National Institute on Aging, and the McKnight Brain Research Foundation. Additionally, Navi disclosed receiving personal fees from MindRhythm.