The disappearance of Neanderthals remains one of the most captivating enigmas in paleoanthropology. Scholars have proposed various theories, ranging from climatic changes to conflicts with early modern humans, as factors contributing to their extinction.

Many researchers have speculated that our ancient relatives may have lacked sufficient genetic diversity to adapt to these changing conditions. A recent study supports the idea that a significant reduction in their genetic variety before their extinction played a critical role in their decline.

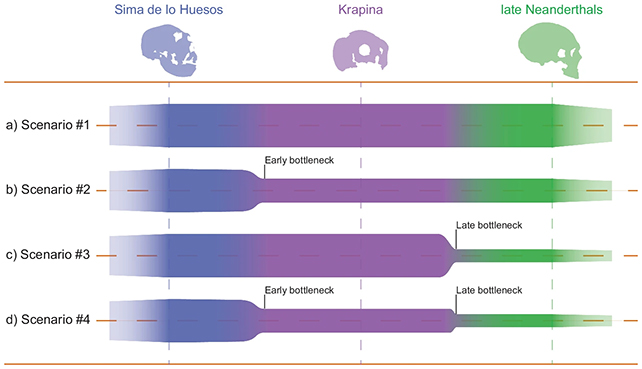

This investigation, conducted by an international team of scientists, employed a distinctive methodology by analyzing ear canal anatomy alongside available Neanderthal genetic data to uncover compelling evidence of a genetic bottleneck that occurred roughly 100,000 years ago.

By examining the morphology of the ear’s semicircular canals in fossils from Europe and western Asia and comparing these with those of contemporary humans, the researchers assessed the relative diversity of body types among various human groups.

According to anthropologist Rolf Quam from Binghamton University in New York, “The formation of inner ear structures is tightly regulated by genetics since they are fully developed at birth.” He notes that variations in the semicircular canals serve as an optimal proxy for examining evolutionary relationships among species over time, reflecting inherent genetic differences.

The Croatian fossil site of Krapina, dating back 130,000 years, was crucial to this research, alongside several late Neanderthal sites in France, Belgium, and Israel (dating from 41,000 to 64,000 years ago).

It appears that a significant event occurred between these two periods, affecting genetic diversity, as indicated by changes in ear canal structures. This suggests a substantial decrease in population numbers prior to around 40,000 years ago, marking the impending extinction of the Neanderthals.

While this research does not delve into the reasons behind the decline in genetic diversity, several hypotheses have emerged over time, ranging from climate shifts to heightened competition.

Mercedes Conde-Valverde, an anthropologist at Alcalá University in Spain, remarks, “By incorporating fossils from a broad geographical and chronological spectrum, we were able to create a detailed picture of Neanderthal evolution.” She emphasizes that the stark reduction in diversity between the Krapina sample and later Neanderthals provides compelling evidence of a bottleneck event.

However, while the study clarifies some aspects, it also raises new questions. The Krapina fossils displayed an unexpected degree of diversity, reminiscent of much older samples over 430,000 years old, challenging the common belief in an earlier genetic bottleneck influencing Neanderthal evolution, thus making a recent decline in diversity more plausible.

The research team is eager to extend their analysis of ear structure across more samples and locations worldwide to uncover further insights into the lives, migrations, and eventual extinction of our distant relatives.

Quam states, “This study represents a groundbreaking method for evaluating genetic diversity within Neanderthal populations.”

The findings have been published in Nature Communications.