Do you remember the moment you first realized that death is inevitable? This realization serves as a pivotal milestone, marking the understanding that your time on this planet is finite. Life has unfolded before us, and it will continue in our absence.

As we mature, our comprehension of death develops gradually, ultimately leading to the acceptance of our own mortality—an undeniable yet unpredictable reality. Typically, children between the ages of six and ten start to grasp the concept that their existence is unmistakably limited.

Interestingly, humanity has only recently begun to fully understand its own mortality. There was a time when we operated under the assumption that human life was eternal. We are now awakening to the reality that events began long before our time, and our species, too, could someday vanish, leaving the universe to continue without us, devoid of any reminders of what we held dear.

The anti-war activist Jonathan Schell referred to this awareness as the ‘second death’. As we grow, we grapple psychologically with our individual ‘first death’—our personal end—while simultaneously confronting the unsettling truth that humankind, as a whole, did not always exist and will not endure indefinitely.

Throughout most of human history, this realization was absent. People tended to diminish or deny the concept of beginnings and endings that extended beyond their personal experiences, often clinging to the notion of eternity. It was once permissible to believe that, on a grander scale, time lacks true limits; that in the vast expanse of eternity, everything—no matter how unlikely—would eventually recur. This belief provided comfort, as the thought of eternity suggested that nothing truly dies and that all lost things could return.

However, the concept of eternity has become increasingly irrelevant, with evidence demonstrating broader mortalities that exceed our own. We now understand that life on Earth began and will eventually meet its end as our Sun ages. This notion represents a ‘third death’. Beyond that, even the Universe is bound by time: it began with a cosmic explosion and is expected to ultimately face its demise as well, leading to the so-called ‘fourth death’. Thus, we confront multiple layers of mortality at grand scales.

We are in the early stages of reconciling this awareness of finitude—a historical shift that may one day be likened to the Copernican Revolution. Nearly 500 years ago, Nicolaus Copernicus reshaped our understanding by demonstrating that Earth is not at the center of the universe but revolves around an ordinary star within an incomprehensibly vast cosmos. It took generations to recognize and name the implications of Copernicus’s findings, and similarly, we are just beginning to understand the significance of the various mortalities we inhabit. With profound revolutions, it often requires time for society to adapt and appreciate the changes to our perspective.

Notably, while Copernicus made us feel small in the vastness of space, recognizing the endpoints of time could reverse that sentiment. It suggests that our actions may hold greater cosmological significance than we previously assumed—a transformation where one paradigm can undo another.

Why is this important? Abandoning the idea of eternity can actually be invigorating. It implies that our actions on Earth hold weight beyond our fleeting lives. By recognizing that time has boundaries, modern science highlights a critical truth: what comes next in our lives might have lasting impacts. If time is finite, history cannot repeat itself; therefore, certain choices become irrevocable.

Historically, people encountering the edges of the unknown often assumed that if something was beyond their sight, it lacked limits. Faced with immense concepts, humanity has often erroneously equated extreme size with boundlessness. Time was similarly misconstrued; for centuries, what was uncharted in geography was also seen as eternal in temporal terms—the indistinct beyond of measured reality.

Although the Abrahamic faiths imposed some limits on time with their concepts of creation and final judgment, eternal perspectives still permeated these beliefs. Earthly existence was viewed merely as a transient phase nestled between two eternal states: the unending before and after promised by divine creation.

The endurance of the idea of eternity may partly be attributed to the comfort it provides. In an infinite timeline, possibilities are repetitively realized, allowing unprecedented changes and irreversible losses to fade away. Everything appears cyclical; what we gain can be regained, and what we lose may eventually be recovered.

Nonetheless, evidence supporting the rejection of eternal time has been accumulating gradually. Humanity’s ability to perceive and understand our world has evolved, especially as we developed tools that allow us to observe beyond immediate realities. Before advancements widened our observational capacities, it was difficult to dismiss the notion that beyond our tangible experiences, time could be limitless.

Our imagination often fails to encompass such extensive epochs, making it easy to presume they lack boundaries entirely.

The concept of the ‘god of the gaps’ illustrates how the supernatural diminishes as our understanding of the universe expands. A similar progression has occurred regarding eternal time; as exploration and inquiry have ventured deeper, we have unveiled the beginnings—and potential endings—of Earth, life, and the Universe itself, slowly replacing eternity with finite timelines. With each discovery, eternity has retreated further into obscurity.

Even today, many forget that the incomprehensibly vast spans revealed by modern science—termed ‘deep time’—differ from true eternity. The human capacity to envision such expansive durations is limited, and thus it seems easy to assume they lack any type of boundary.

Acceptance of such enormities in time would have been unimaginable in earlier epochs, such as before the advent of radio telescopes and radiometric dating. A millennium ago, although it was evident that human lives are not eternal, there was still considerable uncertainty about whether time beyond familiar limits does not simply loop indefinitely.

This belief had a significant impact on behavior. If events were destined to reset, regardless of present actions, then every accomplishment would eventually fade. With this mindset, Roman statesman Cicero asserted that striving for enduring legacies was largely futile.

Before comprehensive archaeological records connected insights across continents, it was impossible to disprove the notion that human history had been an unbroken cycle, exempt from definitive beginnings or substantial transformations.

We idealize a time before humanity cultivated agriculture or developed writing and a period afterward when some humans did.

In a similar vein, prior to comprehensive geographical mapping, individuals could convincingly argue that everything significant documented locally had previously occurred elsewhere, only to rerun cyclically in undiscovered territories.

Philosopher Thomas Hobbes, in his work Leviathan (1651), illustrated the shift from a chaotic ‘state of nature’ to a structured ‘social contract’. This can now be viewed as a transition from prehistory to history. It evokes images of a time devoid of humans engaging in agriculture or writing, and a time thereafter when some began to do so. However, Hobbes contended that this pre-civilizational condition was never universally applicable across the globe.

For Hobbes, history appeared as a cyclical, rather than a ruptured continuum. Regions might oscillate between differing states, but from the planet’s perspective, all occurrences have already been exhibited elsewhere. Thus, he believed that humanity’s collective narrative cannot diverge from its extensive history.

Intellectuals of Hobbes’s generation—such as Francis Bacon and Edmond Halley—noted that although innovative inventions appeared, they could not eradicate a lingering suspicion that these activities had already transpired, numerous times, by forgotten civilizations over eons. Eternity loomed on the horizon, within undiscovered territories.

In the 18th century, perspectives began changing, albeit not without resistance.

Throughout the 1700s, naturalists initiated investigations into Earth’s past to situate the present in the overarching timeline. Geology was beginning to emerge as a science. Initially, geologists expected to unearth evidence suggestive of permanence throughout Earth’s history—presuming that remnants of contemporary life could also be found in the planet’s ancient strata. Some speculated that excavating to Earth’s core might reveal human fossils.

However, as scientists systematically studied the Earth, uncovering fossil records, they discovered no organic remains in the oldest layers, and the skeletal forms changed dramatically the further back in time they examined. Amazingly, fossilized humans were notably absent from more ancient sediment, suggesting that creatures resembling us appeared only notably later—save for a misunderstood giant salamander skeleton previously thought to be human.

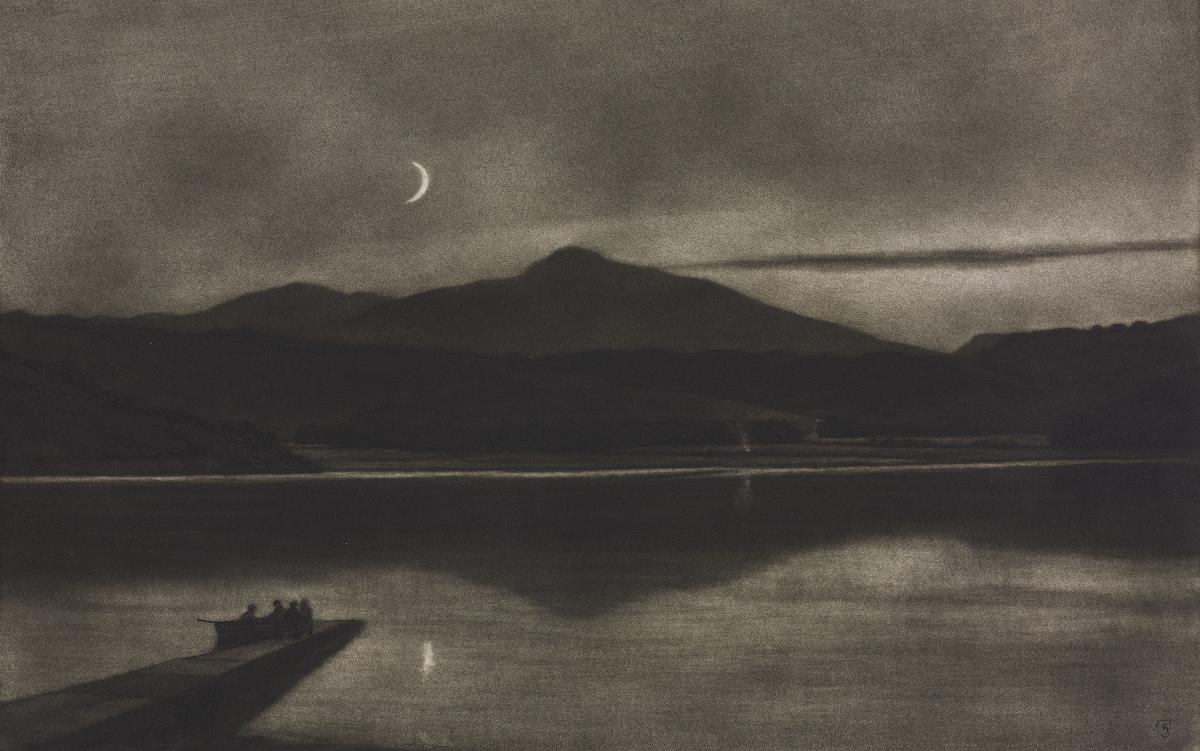

Homo diluvii testis: a fossil believed to be a giant salamander discovered in a German limestone quarry, once thought to represent the remains of a child from the Biblical flood. Image source: BnF, Paris

Amidst these explorations, the French polymath Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, in the 1770s proposed one of the first physical theories that predict both Earth’s historical and future trajectories. He theorized that our planet was steadily losing its original internal heat—having been formed through molten processes—and was inevitably heading toward a frozen demise.

Buffon conducted experiments in his rustic forge, heating iron spheres to measure how long they took to cool. He scaled these findings to estimate the size of Earth, concluding it to be approximately 74,832 years old, with life emerging around 35,983 years ago and potentially remaining habitable for another 93,291 years. Later methods would refine these figures, but at the time, outlining Earth’s history was a crucial beginning to comprehending its finite existence.

Hutton claimed the planet has no visible beginning or end throughout its history.

Shortly after Buffon’s revelations, Scottish geologist James Hutton proposed that only observed processes should explain Earth’s features. However, this line of reasoning led him to assert that Earth’s landscape has remained fundamentally unchanged over time. Hutton famously declared that geologists detect “no vestige of a beginning — no prospect of an end.” He doubted evidence of any era when Earth lacked life, claiming it to be a consistent system that never undergoes radical alterations.

Enthralled by the vast timescales required to shape mountains through gradual processes like erosion, Hutton proclaimed that Earth’s history was not only long but fundamentally limitless. Although often credited as the ‘discoverer of deep time’, this label is misleading; Hutton focused on an unchanging continuum, while the reality of eternity suggests that nothing substantial ever evolves.

This viewpoint recycled the notion of eternity, blending it into the mists of geological epochs. Yet, despite Hutton’s perspective, Buffon’s theory—emphasizing Earth’s definitive timeline—gradually triumphed. While Buffon’s methods were rudimentary and his results often inaccurate, he laid essential groundwork; his attempts to recreate Earth’s evolution in miniature can be traced to today’s advanced climate modeling practices.

Ultimately, Buffon’s quest for Earth’s historical boundaries opened new avenues for understanding life’s narrative as one that unfolds with actual beginnings and irreversible transitions.

It became clear that everything amenable to human observation or biological progress could not have continually transpired in an infinite past, thereby liberating the future from cyclical assumptions. Hopes for entirely new phenomena—never before witnessed—could take root.

Conversely, this realization applied to extraordinary global challenges, including potential disasters with unprecedented impacts.

In 1777, Buffon pondered the implications of a catastrophic event that could obliterate all life on Earth. He conjectured that life would re-emerge and rapidly replenish the planet, presuming that it would consist of the same species that existed before. However, even as Earth’s timeline achieved clarity, the trajectories of its myriad species remained uncertain. Although planets were understood to possess distinct origins and lifespans, it was not yet accepted that species underwent similar transitions.

Scientific understanding about species and their origins remained nebulous, leading to misconceptions regarding their permanence. In the early 1800s, naturalists entertained the idea that intricate beings could spontaneously come into existence without ancestors. Hutton’s followers envisioned a day when dinosaurs might make a triumphant return. Others speculated that the first humans simply emerged from primordial muck, requiring no parental lineage.

Darwin showed that we are the result of time, not mere happenstance.

The arrival of Charles Darwin shifted this paradigm. Following the publication of On the Origin of Species in 1859, the notion that complex organisms could emerge from nothing became untenable. Darwin established that our existence was contingent on countless predecessors—an intricate web of ancestry spanning back to life’s inception. This understanding underscored why individuals within a species could not materialize at random; each requires a lineage extending indefinitely into the past. Darwin validated that species, too, follow their own timelines—they are born, endure, and eventually fade. Their narratives unfold within a framework of causality, making choices and actions in the present carry significant consequences, forever altering Earth’s future.

The concept of eternity persisted in other realms as our awareness of the universe’s expanse expanded. Following the Copernican Revolution, planets became the sites where hopes of infinite recurrence and, consequently, immortality could be projected.

As astronomy confirmed that our Earth is merely one of innumerable entities, it initially instilled a sense of smallness but not solitude. Renowned thinker Blaise Pascal captured this paradox, expressing that the ‘eternal silence of these infinite spaces terrifies me’; yet his fear stemmed not from isolation but rather from the notion of being insignificant in the face of potentially infinite inhabited worlds. Pascal speculated that every globe contains forms of life akin to ours, leading him to contend that all earthly elements must cyclically recur ‘without end and without cessation’. What troubled him was how mundane this eternal cycle rendered our existence.

Pascal was not alone in this perspective. Faced with a Universe far vaster than previously imagined, many assumed it was consequently limitless. Theologian Henry More echoed this, asserting the existence of endless Earths and countless forms of humanity. In these cosmic realms, nothing was unique, and nothing was mortal.

Initially, the Copernican Revolution did not diminish humanity’s self-importance; it inflated it to grand proportions. These ideas persisted until at least the early 20th century.

Consider the case of Arnold Taylor, a reverend from a quaint English village. In 1901, he penned a letter to a scientific magazine expressing concern after reading that there might not be humans residing on other planets. Such an assertion, he felt, was too sweeping to be reasonable.

A century ago, many believed other planets were populated by humans.

Disturbed, Taylor sought insights from astronomers—whom he referred to as ‘planetoscopists’—to clarify. He pointed to Mars as an example, suggesting that experts probably agreed on the likelihood of human habitation there.

This perspective was shared broadly; many assumed that life on other planets mirrored earthly existence, presuming that everything occurring on our world also transpired in others.

By this juncture, the concept of time had expanded beyond Earth to encompass the entire solar system. Thanks to advancements in thermodynamics, the inevitability of our Sun’s demise had become clear, eliminating the prospect of life on its orbiting planets indefinitely. Still, the universe beyond our solar system was largely considered boundless and timeless.

Despite Darwin’s revelations suggesting otherwise, many continued to harbor hopes for the continuation of humanity among the stars. With an eternity’s worth of chances, even the most improbable conditions could manifest repeatedly. As Nobel laureate Robert A. Millikan once claimed, there would always exist, somewhere in the cosmos, an Earth where ‘the development of man still may be taking place a billion years hence.’

Lemaître proposed the Universe arose from a monumental explosion.

In an eternal cosmos, such resurrection seemed plausible. Even Darwin himself hinted at the notion of an evolutionary ‘fresh start’ following the demise of the Sun. This idea brought comfort, especially as humanity began tomessing with atomic power.

However, revelations pertaining to the universe brought temporal boundaries back to the forefront. Throughout the 1920s, observations from the foremost telescopes unveiled that distant galaxies are moving away from us at remarkable speeds—indicating an expanding universe.

This expansion hinted at a cataclysmic inception; it implied a finite conclusion, where energy and matter would ultimately dissipate into nothingness. For the first time, the universe itself was being recognized as having a distinct beginning and an eventual end.

Belgian physicist Georges Lemaître was among the first to theorize this connection, proposing in 1931 that our cosmos emerged from an astronomical explosion. He compared the universe to a firework display, suggesting that as we observe its aftermath, we stand on a ‘cooling cinder’ experiencing the explosion’s remnants.

In 1946, Lemaître published a synthesis of this revolutionary idea; three years later, cosmologist Fred Hoyle referred to it as the ‘Big Bang’ during a British radio broadcast—an appellation that endures to this day.

From the late 1940s onward, Hoyle mounted a defense against this temporal framing of the universe’s chronology, mirroring Hutton’s earlier efforts but on a cosmic scale, seeking theories that accounted for the universe’s expansion without invoking the concept of origins. However, the Big Bang model began to gain traction.

This shift carried significant consequences. In an eternally structured cosmos, the assumption prevailed that life had always existed; it merely circulated, consistently reappearing across different cosmic realms. Previous generations had speculated about concepts such as ‘astroplankton’ or ‘space spores’ that could link life across different areas of the universe seamlessly.

These theories suggested that ‘organic beings are eternal like matter itself,’ painting a picture of a cohesive, immortal family unbound by isolation. When lifetime is perceived as unending, it becomes difficult to fathom an ultimate termination. If life exists everywhere, at all times, it poses virtually insurmountable challenges to annihilation.

We must now confront the idea that life has a definitive origin and is inherently fragile.

The idea of an eternal universe traditionally supported aspirations that our species would reemerge, regardless of the unlikelihood of such scenarios. The anthropologist Loren Eiseley elucidated this notion in 1953, observing that the antiquated ‘idea of an eternal universe’ seemed to guarantee ‘an infinity of time for humanity to arise again and again.’ The comfort provided by this viewpoint allowed many to rest easy.

However, Eiseley soon recognized that evolving evidence for the Big Bang undermined these assumptions. Life could not be presumed to circulate indefinitely through the universe; instead, it must face the possibility of an origin within a specific timeframe, marking it as a delicately precarious phenomenon. Over time, evidence began to suggest that, eventually, the cosmos would exhaust its available energy, rendering the emergence of complex life impossible.

The Big Bang ushered in a new wave of unsettling inquiries. As Enrico Fermi famously queried in 1950, “Where is everybody?” He was speaking about extraterrestrial life. The enduring question loomed large. If the universe is inherently finite, how likely was it that we had not been visited already?

This spurred alternative deliberations; perhaps we exist in a cosmic epoch that precedes the proliferation of life throughout the universe. Eiseley further articulated this concern, noting how there had not yet been sufficient time for life to have effectively distributed beyond even our known galaxies.

The recognition of temporal limits posed radical possibilities for the future. For Buffon’s era, the ramifications occurred on a planetary scale; now, they unfolded on a cosmic level. It became plausible to propose that the cosmos’ evolution could yield a future dramatically different from its past and present. Could biology be the catalyst for such transformations?

During this time, humanity was making advancements in rocket technology. This progress sparked more questions: Are we the first to dream of interstellar travel, or are there countless others who have attempted and faltered throughout history? What if atoms and rockets led not only to space exploration but to catastrophic collapses?

Launched in the 1960s, the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI) has yet to discover any signs of life; only the pervasive silence of the cosmos remains. As the second millennium progressed into the third, continuous findings indicated that the emergence of intelligent life, much like our own, is no guaranteed certainty. We appear to be a product of chance—a remarkable outcome of the cosmic ‘roulette wheels’ of star systems, as Stansław Lem aptly stated.

This may provide insight into our inability to hear the chatter of distant civilizations. Perhaps we are the first improbable beings asking ourselves: Could we be the first?

If life on Earth is indeed rare and unprecedented, its extinction could signify a profound loss for the cosmos. Without a lineage of predecessors, we can only hypothesize about our potential. There are no past models to inform our future paths, nor are there assumed boundaries on what we might ultimately accomplish.

Demonstrating that time has distinct beginnings and ends took centuries of investigation, yet its implications are only beginning to settle in. It is through the understanding of deep, albeit finite, time that we have come to realize that we cannot hide behind the idea of eternity. There will be no repeats—no other Earths. To die here is to die eternally, and we can only speculate about whether other forms of intelligence exist within the vast universe to carry on from our demise. Eiseley aptly remarked: ‘The same hands will never twice build the golden cities of this world.’

When we come to terms with our individual mortality—the ‘first death’—we face a singular chance to leave a mark on this world. This notion of uniqueness extends planetarily, and thus we must accept that the same principle applies to life as a whole.

While humanity’s desire for immortality endures, we must now find it within the Many-Worlds theories of quantum physics—or in other hypothetical realms. Where once life seemed assured of repeating on distant continents or other planets, we are now compelled to seek the idea of recurrence in parallel universes.

The extent to which we have dispelled the notion of eternity—from uncharted regions to the fringes of spacetime—reflects the increasing weight of the present moment and our actions within it.

If the Copernican perspective reshaped our view of space, learning to navigate time is giving rise to something novel. The initial lesson was mediocrity; the emerging lesson is the fragility of existence.

It is the world’s demise that secures the lasting impact of our actions.

Moreover, this newfound understanding of our temporal position appears to have converged at a critical moment. Until recently, thinkers regarded deep time as diminishing the significance of the present, wherein ‘now’ seemed inconsequential amidst the vast expanse, gradually washing away legacies over the long term.

This perspective is fundamentally flawed. What unfolds today carries potentials for legacies that are not only irreversible but also non-inevitable, the repercussions of which will be felt for millennia. Time is not merely deep; it is also deeply fragile. This sobering knowledge requires urgent acceptance. We must harness it now and secure a future for ourselves, or risk having none. The luxury of infinite retries does not exist.

Some might view it as disheartening to acknowledge that all things face death. But in doing so, they overlook a vital truth: it is only within a mortal framework that consequences can echo through time. Thermodynamics illustrates that the universe’s available energy is finite; every action contributes to depleting that resource. Thus, the total actions that could possibly transpire are bound—regardless of how immense that finitude may be. Choosing one action over another leaves an enduring cosmic legacy, regardless of the perceived significance of the choice. While legacies can be erased, doing so consumes effort and energy, which is not infinite.

Therefore, while the first realization is that existence itself has boundaries, the more profound realization is that this endows our actions with enduring significance in a cosmic context. It is through the world’s inevitable decline that the timelessness of our influence is secured.

This concept applies to both modest aspirations and grand ambitions alike. We might term it the energetic imperative: do not squander energy; instead, direct it toward what is beautiful, joyful, and vibrant! Every moment we do not, the aging universe diminishes in vibrancy and color.

This supremacy of finitude—this encompassing awareness of larger mortalities than our own—is inherently energizing. Like a child coming to grasp her ‘first death,’ this acknowledgment might be an integral aspect of growing up.

In the end, while eternity may entice and stifle, the recognition of finitude brings enlightenment, illustrating that our choices today carry immense weight. If the cost of eternal life is the relinquishment of our agency, I would choose agency time and again.