Subscribe to the Smarter Faster newsletter

A weekly bulletin showcasing groundbreaking ideas from the brightest minds in various fields

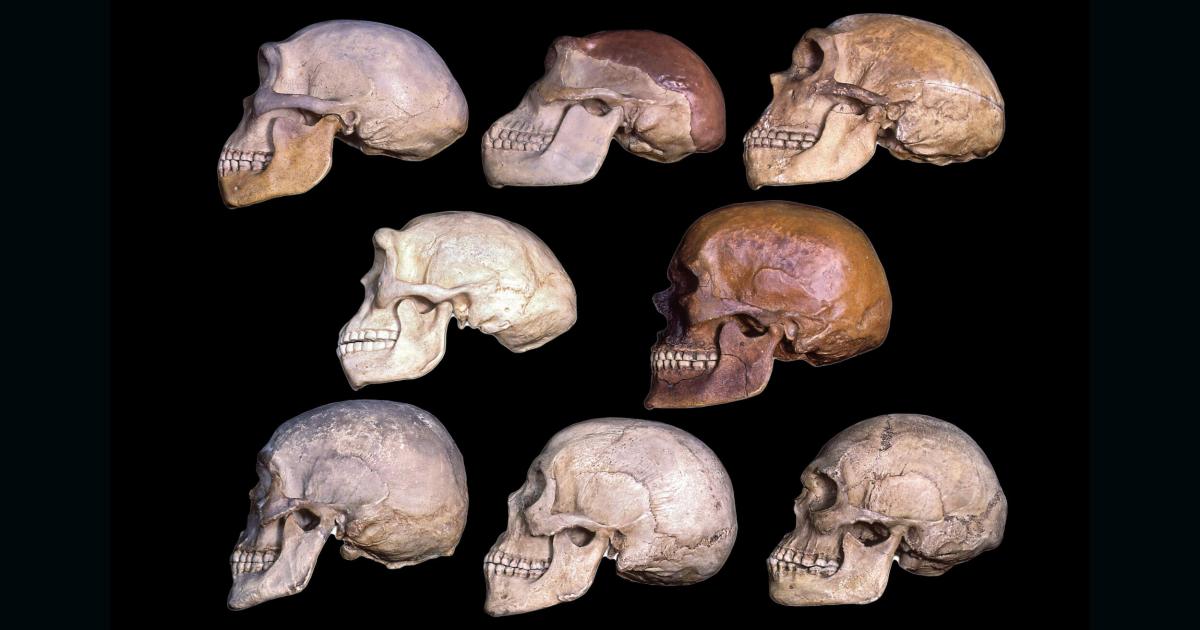

Encephalization, defined as the increase in brain size in relation to body mass, plays a crucial role in the evolution of humans. However, the specifics of how this phenomenon unfolded remain a topic of debate. Research comparing the cranial capacities of early modern humans to different hominin species indicates varying perspectives: some scientists assert a gradual increase in brain size over time, while others propose that it grew in spurts interspersed with extended periods of stasis.

This complexity is further heightened by uncertainties regarding the evolutionary processes involved, including the branching of lineages and the division of ancestral species into distinct groups, which have led to the observed variability in brain size among early humans and other hominins.

Recent research offers new findings on the patterns of brain development both within and across hominin species. This study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, shows that brain size increased within specific species, with the most pronounced growth occurring in recent human ancestors.

Understanding Brain Expansion

A team of evolutionary anthropologists led by Thomas Püschel at the University of Oxford examined fossils of early human ancestors (hominins) that date back to 7 million years ago, creating the most comprehensive dataset on brain evolution to date. Due to the incomplete nature of fossils, they employed advanced computer modeling techniques to hypothesize the missing information.

Their findings reveal that while species with larger body sizes tended to have bigger brains, there was not a consistent increase in brain size with body mass. Instead, brain size generally increased steadily within individual species, driven by a combination of genetic, environmental, and behavioral influences rather than any single factor.

Furthermore, the research indicates that brain growth accelerated in more recent lineages, suggesting varied intensities and durations of selective pressures within specific hominin groups, which challenges the notion of a singular driver behind brain evolution.

“The diversity we observed indicates varying selective pressures within individual hominin lineages,” Püschel told Big Think. “Our results imply an increasing trend in brain size over time within species, supporting hypotheses suggesting a co-evolutionary feedback loop involving social structures, culture, technology, and language.”

These interactions likely reinforced certain selective pressures, enhancing cognitive abilities that facilitated more complex behaviors and, in turn, selected for larger brains.

Püschel also noted that genetic mutations might have impacted brain growth capacity, though it’s more plausible that a mix of genetic, ecological, and behavioral factors collectively molded encephalization across different species and eras.

The team is currently conducting further analyses utilizing the dataset they have compiled. “We are beginning to incorporate environmental and climatic variables to investigate how these factors might have affected brain evolution,” he says. “While many longstanding hypotheses have connected encephalization with climate, a clear consensus has yet to be established. Our method enables us to test these ideas with greater rigor.”

In a recent preprint, Püschel and colleagues published preliminary evidence suggesting that colder and more variable climates could have driven brain enlargement within species by fostering adaptations that helped counteract hypothermia.

Subscribe to the Smarter Faster newsletter

A weekly bulletin showcasing groundbreaking ideas from the brightest minds in various fields