Subscribe to CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter.Delve into the cosmos with updates on remarkable discoveries, cutting-edge scientific progress, and more.

CNN

—

Various bird species, including hummingbirds, peacocks, and parrots, showcase vibrant colors, but birds-of-paradise stand out for their extraordinary and bright shades of emerald, lemon, cobalt, and ruby. Recent research has uncovered that these exquisite birds are capable of conveying hidden color signals that remain invisible to human eyes.

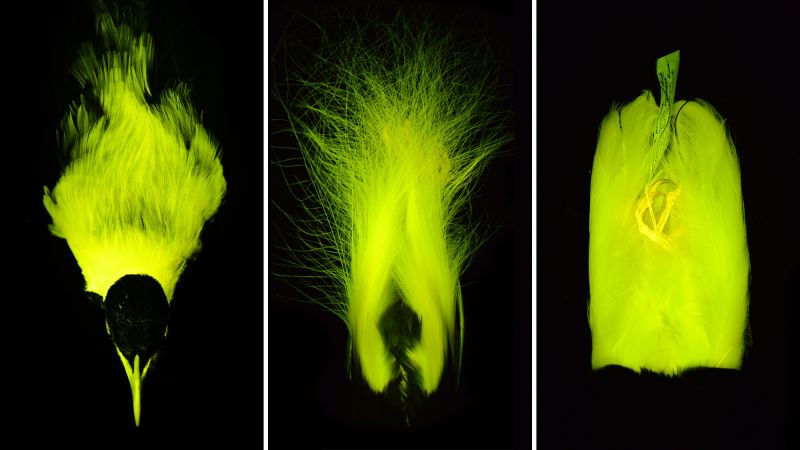

Under blue and ultraviolet (UV) light, certain parts of birds-of-paradise glow, revealing bright green or yellow-green hues, according to a study released on February 12 in the journal Royal Society Open Science.

Living beings emit light through two primary mechanisms: bioluminescence and biofluorescence. For example, bioluminescence (as seen in fireflies) is the result of a chemical reaction involving luciferin and luciferase. On the other hand, biofluorescent organisms absorb high-energy light wavelengths (such as UV, violet, or blue), then re-emit the light at a lower energy wavelength.

The research highlighted biofluorescence in 37 out of the 45 recognized species of birds-of-paradise, typically found in the secluded tropical forests and woodlands of Papua New Guinea, eastern Indonesia, and certain regions of Australia. When illuminated with blue and UV light, these birds’ white and bright yellow feathers emit colors that may play a role in territorial conflicts or courtship displays.

Birds are well-known for their remarkable color vision, and various avian species, including pigeons, turkeys, ducks, and geese, can detect light in the UV spectrum. While little is understood about the visual capabilities of birds-of-paradise, related species, such as crows, ravens, and certain magpies, have been shown to be sensitive to violet light wavelengths. For these birds, fluorescent patterns would appear as bright beacons in darker environments, according to study authors.

“The research is rigorously designed, addressing the diversity within the birds-of-paradise group and their close relatives,” stated Dr. Jennifer Lamb, an associate professor of biology at St. Cloud State University in Minnesota. Lamb, who is investigating biofluorescence in amphibians and reptiles, was not part of this particular study.

“What’s fascinating about biofluorescence is that, although it serves as a visual signal, it remains a relatively overlooked domain in many animal groups,” Lamb commented. “This suggests that we may have underestimated the potential for visual signaling and communication, especially since it isn’t detectable by our human eyesight.”

While birds-of-paradise are famous for their vivid colors, the biofluorescent aspect of their visual communication was previously unrecognized and raises intriguing questions about their use of visual cues, according to lead author Dr. Rene Martin.

“This finding is just one additional piece of a larger puzzle,” she explained to CNN. “If it can be identified in a group that is arguably well-studied, similar discoveries are likely present elsewhere in the animal kingdom.”

Over a decade ago, senior author Dr. John Sparks, a curator in the ichthyology department at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York City, discovered biofluorescence in several fish species. This prompted him to investigate the prevalence of this characteristic across other animal groups, as noted by Martin, a fellow fish biologist and an assistant professor at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln.

Utilizing a vast collection of bird specimens curated at AMNH, Sparks conducted a preliminary review using blue light, which confirmed the presence of fluorescence in birds-of-paradise. However, it was not until Martin began her postdoctoral research at the museum in 2023 that a more comprehensive investigation took place.

Partnering with Sparks and doctoral student Emily Carr from the museum’s Richard Gilder Graduate School, Martin re-examined the birds-of-paradise samples found in AMNH’s repository.

“I essentially employed high-powered blue and UV flashlights to survey the collection,” she recounted. During her examination, she donned special goggles designed to filter out blue light, allowing her to observe only the fluorescence emitted by the birds-of-paradise.

The researchers then transferred these birds into a dark room where they captured images and assessed light emissions. Depending on the species, fluorescence appeared in various body parts, including the birds’ bellies, chests, heads, and necks. Some species displayed elongated, glowing plumes, radiant bills, or shimmering spots inside their mouths.

“Often, the fluorescent patches were surrounded by darkly pigmented feathers, providing a striking contrast,” Martin noted. “Many of these birds-of-paradise have also developed a unique ultra-black feather that absorbs a significant amount of light. This is intriguing, considering that non-biofluorescent birds-of-paradise do not possess this ultra-black feather.”

With over 11,000 bird species recognized, only a limited number of groups are known to exhibit fluorescence. Previous observations of biofluorescence have been reported in auks, bustards, owls, nightjars, parrots, penguins, and puffins, yet little is understood about how these species leverage biofluorescent signals, as highlighted by the study’s authors.

“In parrots and birds-of-paradise, it’s speculated that they may utilize these signals for communication or courtship displays,” Martin remarked.

However, for some other groups where biofluorescence has been detected, scientists remain uncertain of its purpose or whether it serves any function at all, Martin added. “It might be a beneficial protein enhancing feather structure that coincidentally causes biofluorescence.”

Biofluorescence likely exists in many more species than previously recognized. Recent studies have found this trait in fish, salamanders, sea turtles, and various species of mammals and marsupials.

“Exploring biofluorescence is crucial to understanding the evolutionary pathways of communication across various species,” Lamb emphasized.

“Additionally, there are potential implications for advancements in fields like medicine or technology,” she noted. The discovery of green fluorescent protein in jellyfish, for instance, is now a vital tool in medical research for tracking embryonic development and investigating cancer growth among other cell types.

“If biofluorescence appears throughout the tree of life, it likely holds significant advantages for the organisms that exhibit it,” Martin stated.

“Whether it is utilized for signaling in birds-of-paradise or for camouflage in another creature, it represents an additional evolutionary strategy for survival and reproduction among species.”

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and media producer whose work has been featured in Live Science, Scientific American, and How It Works magazine.