The Earth’s inner core, a dense sphere composed mainly of iron and nickel with a diameter of approximately 1,500 miles, may not be entirely solid. Recent research indicates that the outer boundary of this inner core has undergone notable shape changes over the last few decades.

John Vidale, a professor of Earth sciences at the University of Southern California, explains, “It seems that the outer core may be exerting a pull on the inner core, causing some movement.” This new research was published on Monday in the journal Nature Geoscience, highlighting ongoing mysteries surrounding the Earth’s core.

Previous findings from geophysicists have revealed that the inner core does not rotate in perfect synchrony with the planet’s surface. Reports suggest that alterations in the rotation speed have occurred over time; notably, a couple of decades ago, the inner core was rotating slightly faster than the outer layers. Currently, it appears to be spinning a bit more slowly.

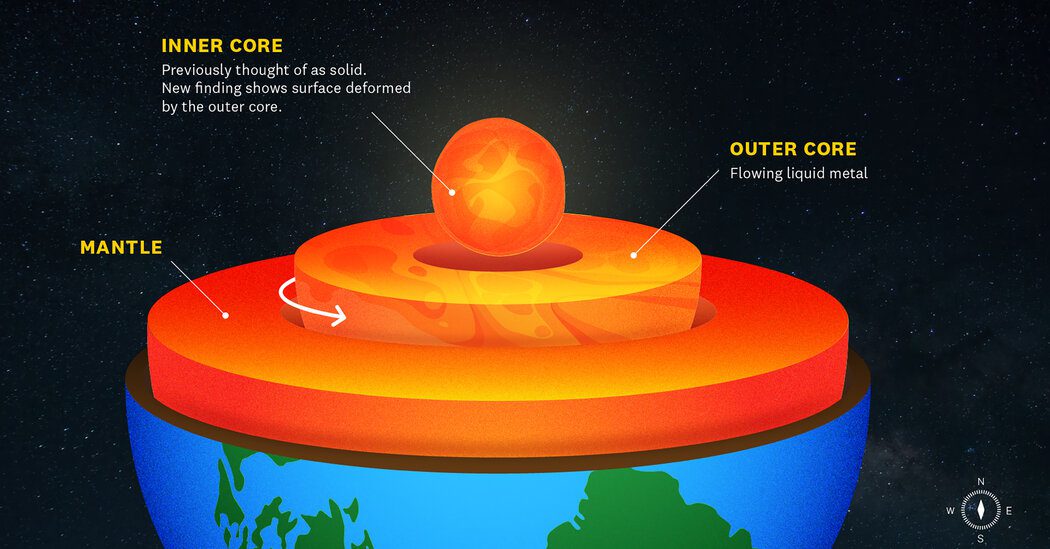

The inner core represents the deepest layer of our planet. Above it lies the crust, which is merely a few miles thick, followed by the mantle that constitutes about 84% of Earth’s mass and extends approximately 1,800 miles downward. This mantle is semi-fluid in certain areas, enabling it to move and create the forces responsible for continental drift. The liquid outer core sits between the mantle and the solid inner core.

Due to the challenges of directly observing Earth’s interior, scientists rely on seismic wave data generated by earthquakes. The characteristics of these seismic waves—such as their speed and trajectory—are influenced by the density and elasticity of the geological materials they traverse.