Deep within the rocky landscape of Morocco, scientists have made an intriguing discovery—a unique species of blowfly that has successfully integrated itself into the lives of termite colonies.

Assimilation in termite communities is rare, but this blowfly has developed a remarkable multi-faceted disguise that effectively deceives termites, enabling its larvae to not only survive but flourish within these colonies.

According to a recent study, such behavior had not been previously documented in this type of fly. The researchers stumbled upon these larvae while investigating termite colonies in the Anti-Atlas mountains of southern Morocco, where the native harvester termites (Anacanthotermes ochraceus) create underground nests.

Roger Vila, an evolutionary biologist at the Institute of Evolutionary Biology in Spain, primarily studies butterflies and ants. Faced with a rainy day that kept most butterflies inactive, his team shifted their focus to ants.

“When we turned over a stone, we were surprised to find a termite mound harboring three fly larvae we had never encountered before,” Vila explains. “The rain must have flooded the lower layers of the nest, prompting the larvae to surface.”

Intrigued, the researchers revisited the site three times, examining hundreds of stones but managing to locate just two additional larvae, found close together in another termite mound.

This rarity suggests that the species is not common, according to Vila. Phylogenomic studies indicate the blowflies fall under the genus Rhyncomya, though further investigation is needed to uncover more about their population and ecological roles.

What has been revealed so far is already quite remarkable.

Termites utilize their antennae to examine and scent newcomers, adeptly identifying potential threats. Specialized soldier termites are equipped with large mandibles to defend against intruders.

With such impressive safety measures, climate control, and reliable food sources, it’s understandable why other insects might attempt to infiltrate their colonies, despite the inherent risks.

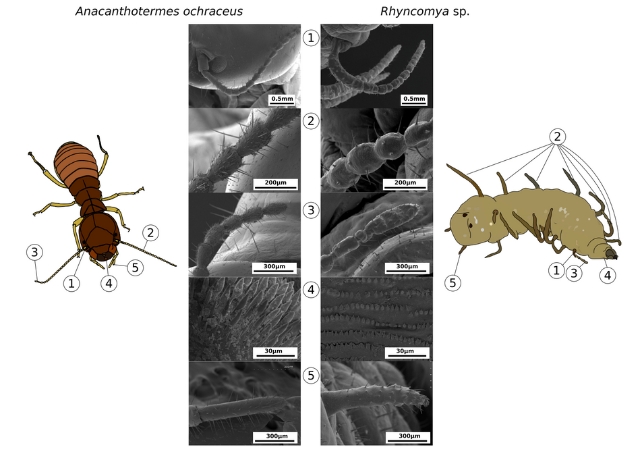

As part of their ingenious camouflage, the blowfly larvae feature a “termite mask” on their rear end. This mask mimics a termite’s head, complete with antennae and palps resembling those of a harvester termite.

Additionally, the mask sports artificial eyes, which closely resemble those of harvester termites. However, as Vila clarifies, these are actually openings for breathing.

“Most termites reside several meters underground and lack visual perception,” Vila elaborates. “Nonetheless, harvester termites venture out at dusk to gather grass and possess functional eyes that the larvae cleverly mimic using their spiracles.”

Alongside the faux termite head, the blowfly larvae boast intriguing ‘tentacles’, which are remarkable imitations of termite antennae, as demonstrated through advanced scanning electron microscopy.

Unlike the faux head, these tentacles appear to serve a purpose; the larvae likely utilize them to communicate with termites.

Thanks to their numerous protrusions, the larvae can interact with multiple termites simultaneously.

These adaptations are impressive, but they still require additional support.

Each termite colony possesses a unique scent shared among its members; without this signature, entry is forbidden. Merely resembling a termite is insufficient if their scent does not match—intruders from other colonies are often met with aggression and can be torn apart by soldiers.

However, these fly larvae are exceptional at adaptation. They not only mimic the scent of their host colony but, as Vila notes, they replicate it flawlessly.

“We analyzed the chemical makeup of these larvae, and the outcome was astonishing: they are indistinguishable from the termites in their colony; they project the same scent,” he states.

In their natural environment, the researchers found the fly larvae residing within the termites’ food chambers. Upon bringing some back to a laboratory termite mound, the larvae instinctively moved toward more populated areas.

Termites demonstrated a keen interest, gathering around the fly larvae and engaging in preening behavior. They even seemed to offer them food.

“These larvae are not only accepted but actively engage with the termites using their antenna-like tentacles,” Vila remarks. “While it hasn’t been definitively proven, the termites appear to provide them with nourishment.”

While some humpback flies (Phoridae) also mimic termites, they do so as adults, unlike the larvae of this blowfly, which indicates these evolved adaptations emerged independently.

“The common ancestor shared by blowflies and humpback flies goes back over 150 million years, a much longer timeframe than the evolutionary gap between humans and mice. We confidently view this as a new instance of evolution leading to social integration,” Vila remarks.

No other species in the genus Rhyncomya exhibit comparable traits or behaviors, suggesting this adaptation occurred relatively swiftly.

This discovery encourages a reevaluation of the boundaries and possibilities of symbiotic relationships and social parasitism in nature,” Vila adds.

“Above all, it reminds us of the vast unknowns regarding the incredible variety and specialization of insects, which play crucial roles in ecosystems.”

The findings of this research were published in Current Biology.