The massive hunk of metal drifted quietly through the vastness of space, hovering above Earth’s vibrant blue surface. With its power sources depleted, its instruments lay dormant, and its communication systems were completely silent. By all accounts, it appeared to be lifeless, leading most back on Earth to relinquish hope for its return.

Most, but not all.

Even though its batteries had run dry, a glimmer of activity suddenly pulsed from within. Its onboard computer, designed with a failsafe mechanism, was programmed to reboot the spacecraft when it detected a complete power loss, utilizing solar arrays for additional energy collection. In an unexpected turn, the small satellite reignited its various sub-systems. Its flight computer came back online, reaction wheels whirled into motion, sensors activated, and the radio antenna resumed sending signals.

“We were all overjoyed! It truly felt like a miracle.”

— Xinlin Li, Principal Investigator for CIRBE

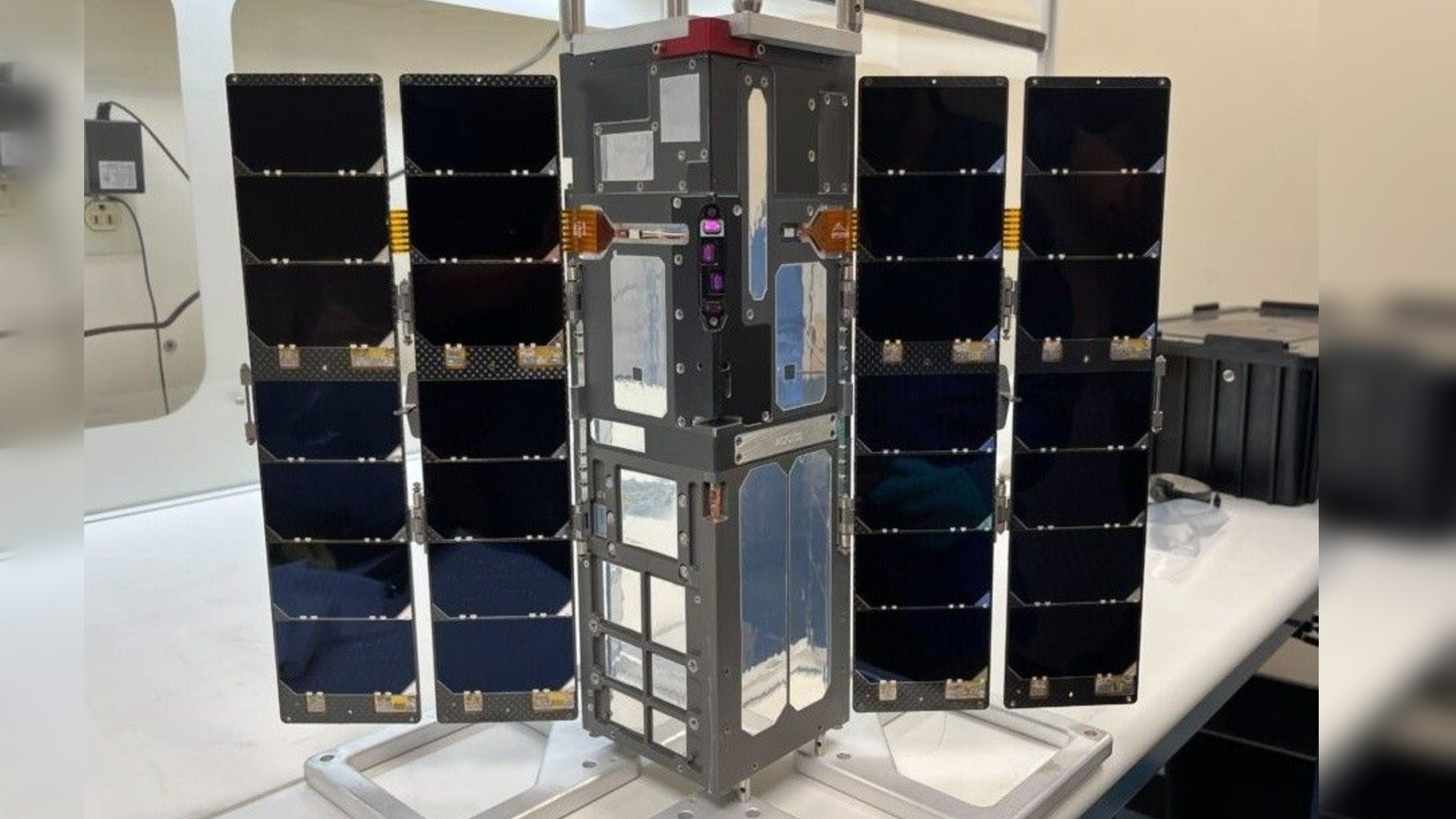

The Colorado Inner Radiation Belt Electron (CIRBE) Experiment was a small cubesat that launched in April 2023 to observe charged particles in the inner Van Allen radiation belt. Its mission was so successful that NASA granted it an extension beyond its initial four-month timeframe. However, on April 15, while orbiting approximately 316 miles (509 kilometers) above the planet, it inexplicably shut down.

It faded into silence, and most assumed that was the end.

“We felt a wave of disappointment – the only silver lining was that the high-energy resolution measurements had yielded substantial data,” Xinlin Li, CIRBE’s lead investigator at the University of Colorado, shared in a Space.com interview.

Then, in May 2024, intense solar storms erupted from the sun, unleashing a barrage of charged particles that collided with Earth’s magnetic field, generating a powerful geomagnetic storm that impacted the Van Allen belts — precisely the phenomena CIRBE was designed to study. Unfortunately, CIRBE was absent during this critical event. As the auroras painted the skies around the world on the night of May 10, Li’s peers found joy in the celestial display, while he stayed behind.

But Li remained resolute.

CIRBE Awakens

Realizing the unparalleled opportunity they missed without CIRBE to monitor the storm’s implications, Li felt disheartened. “I wasn’t inclined to go outside and enjoy the aurora,” he confessed.

Instead, he diligently checked satellite telemetry updates on the SatNog website, quietly hoping for CIRBE to awaken. His optimism was not misplaced; CIRBE had a sibling mission — the Colorado Student Space Weather Experiment (CSSWE), launched in 2012. After going silent for three months in 2013 due to a known communication issue, CSSWE miraculously returned to functionality thanks to a built-in “Phoenix mode” that rebooted the system following power loss.

The cause of CIRBE’s unexpected silence remained unidentified. Li speculated it might have been flash memory corruption and held onto the hope that a reboot would occur. Then, on May 23, an unexpected signal from CIRBE emerged.

“It came back for two-and-a-half days before falling silent once more,” Li recounted. “The reason is still unclear.”

Li’s persistence paid off when, on June 10, CIRBE made contact again and this time, it was here to stay — until its orbit decayed, resulting in reentry into the Earth’s atmosphere on October 4, where it ultimately burned up magnificently.

“We were all ecstatic!” Li exclaimed about CIRBE’s revival. “It was nothing short of miraculous.”

Unfortunately, that miracle had its time limit. The solar storms significantly heated the Earth’s upper atmosphere, causing it to expand and increase atmospheric drag on the cubesat, which ultimately led to its destruction — the very phenomena CIRBE had been sent to study.

“Each time we faced a powerful magnetic storm, it was a mixed blessing,” Li reflected. “We captured dynamic behaviors in the radiation belts and observed novel phenomena, all while witnessing CIRBE’s altitude decline rapidly during each storm.”

A ‘Miraculous’ Return: IMAGE

Thankfully, CIRBE managed to come back online just in time to detect two new temporary radiation belts created by the influx of solar particles in the gap between the two Van Allen belts. Unlike CIRBE’s brief revival, some missions remain in limbo for extended periods before reactivation.

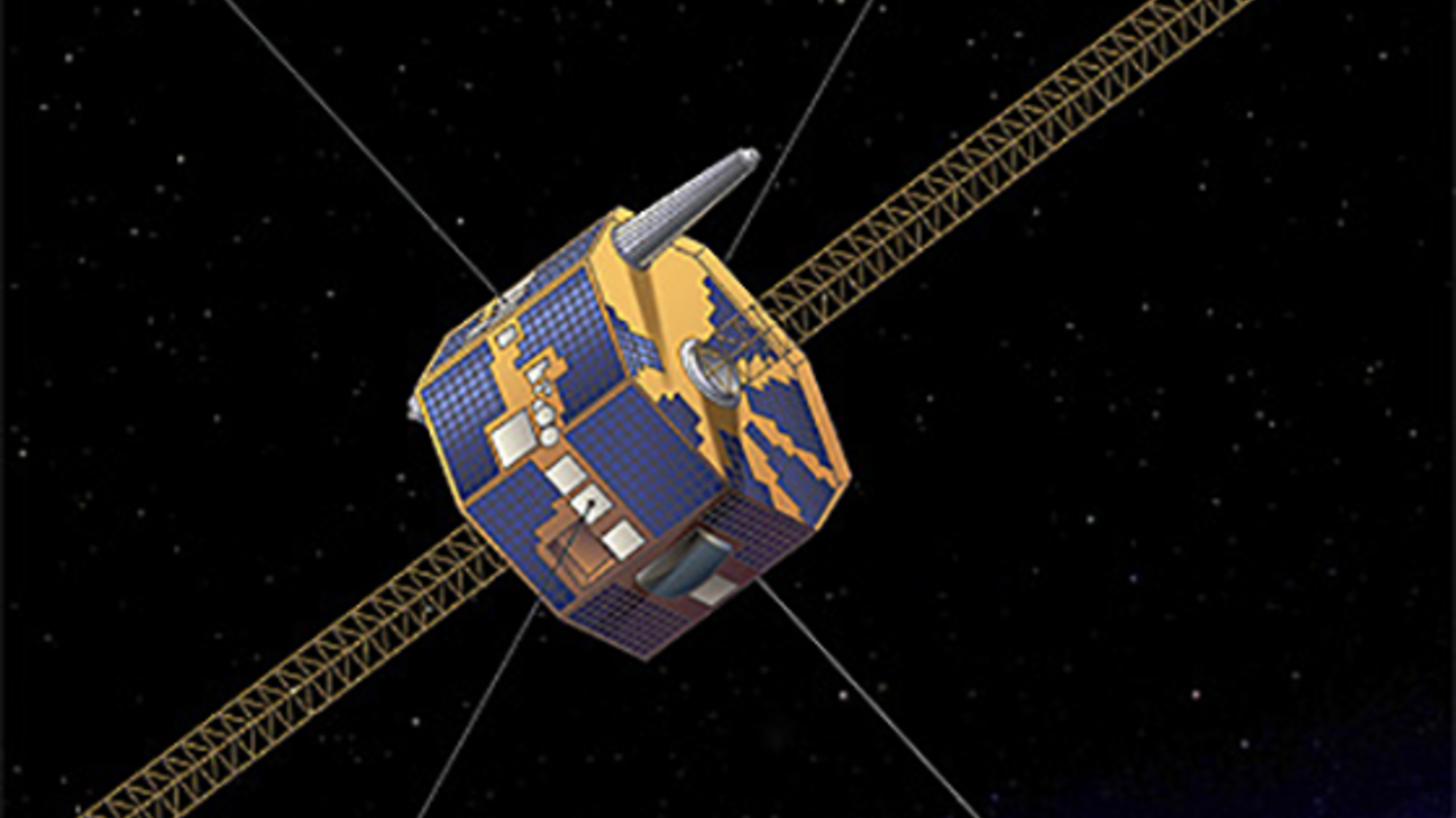

For instance, NASA’s Imager for Magnetopause-to-Aurora Global Exploration (IMAGE) first launched in 2000. Like CIRBE, IMAGE was created to examine solar storm effects on the magnetosphere. For five fruitful years, it delivered exceptional data until it inexplicably ceased functioning one day in December 2005.

With presumed silence from IMAGE, the mission team moved forward with other projects until a surprising turn of events occurred in January 2018: IMAGE reestablished its signal.

An amateur radio astronomer, Scott Tilley, inadvertently discovered IMAGE while searching for a lost military satellite. Upon relaying this astonishing news to Richard Burley, IMAGE’s mission director at NASA, the team promptly worked to confirm the source of the signal, identifying it as IMAGE’s unique ID 166.

Once in command of the spacecraft, they uncovered a striking revelation: electronics damaged back in 2004 by a cosmic ray strike, a phenomenon NASA refers to as a “Single Event Upset” (SEU).

IMAGE’s power distribution unit (PDU) maintained both an A-side and a B-side for redundancy. Following the SEU incident, the A-side failed, necessitating a switch to the B-side. However, when contact was restored in 2018, the PDU was allegedly using its A-side again, indicating that the spacecraft had been intermittently rebooting its systems.

Upon deeper investigation, Burley and the IMAGE team pieced together the mystery. The damage from the cosmic ray had misled the PDU into believing it was still connected to the radio transponder, which had actually failed, resulting in the initial blackout in 2005.

“Spacecraft have a built-in ‘command watchdog timeout’” Burley explained. “This system is programmed to reboot the spacecraft’s computer if it fails to receive commands within a specified timeframe.”

For IMAGE, this timeout was set to 72 hours. However, since the reboot did not reset the PDU, every time IMAGE attempted rebooting, it mistakenly thought it was still operational. As it couldn’t receive any commands from Earth, which assumed it was inactive, the spacecraft kept rebooting indefinitely for 13 long years, akin to being trapped in a relentless loop.

Eventually, the PDU reset itself, returned to the A-side, and power was restored to the transponder, allowing it to connect with Earth once more. This scenario mirrors an individual regaining mobility or speech after a stroke, a remarkable recovery.

Burley noted that cosmic ray strikes are frequent occurrences for spacecraft, with onboard error detection typically resolving minor issues, but multi-bit errors can lead to significant problems. “In fact, two other NASA Goddard spacecraft experienced similar anomalies with their solid state power controllers,” he noted. Fortunately, in those instances, their communications remained intact, enabling diagnostics and repairs to rectify the issues. All affected SSPCs were produced from the same batch, designed with radiation-resistant features.

As for IMAGE, its lengthy period of solitary confinement in space took a toll. On February 24, 2018, communications with IMAGE faltered again, and when the signal was eventually picked up, it was weaker. By May 2018, it was transmitting more robustly but struggled to accept commands from mission control. Finding appropriate hardware to run outdated software from the early 2000s became another challenge for controlling the spacecraft and analyzing its telemetry. The last contact was recorded on August 28, 2018.

A Long Sleep in the Cosmos

The experiences of CIRBE and IMAGE illustrate instances of unintentional shutdown; however, more spacecraft are now being purposefully placed into dormancy. This strategy aids in conserving power during lengthy missions — for example, the European Space Agency’s Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer will enter hibernation for much of its eight-year journey to Jupiter, reactivating upon arrival to explore its frozen moons — Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto.

Totaling the initial endeavors of dormant spacecraft, the European Space Agency’s Giotto mission was among the first. After its historic encounter with Comet Halley in 1986, it was temporarily deactivated for a future rendezvous with Comet Grigg–Skjellerup. Giotto was reawakened on July 2, 1990, to perform a flyby of Earth, utilizing gravitational forces to propel it toward the dual comet, which it ultimately approached on July 10, 1992, before being turned off once again to rest.

Reviving WISE

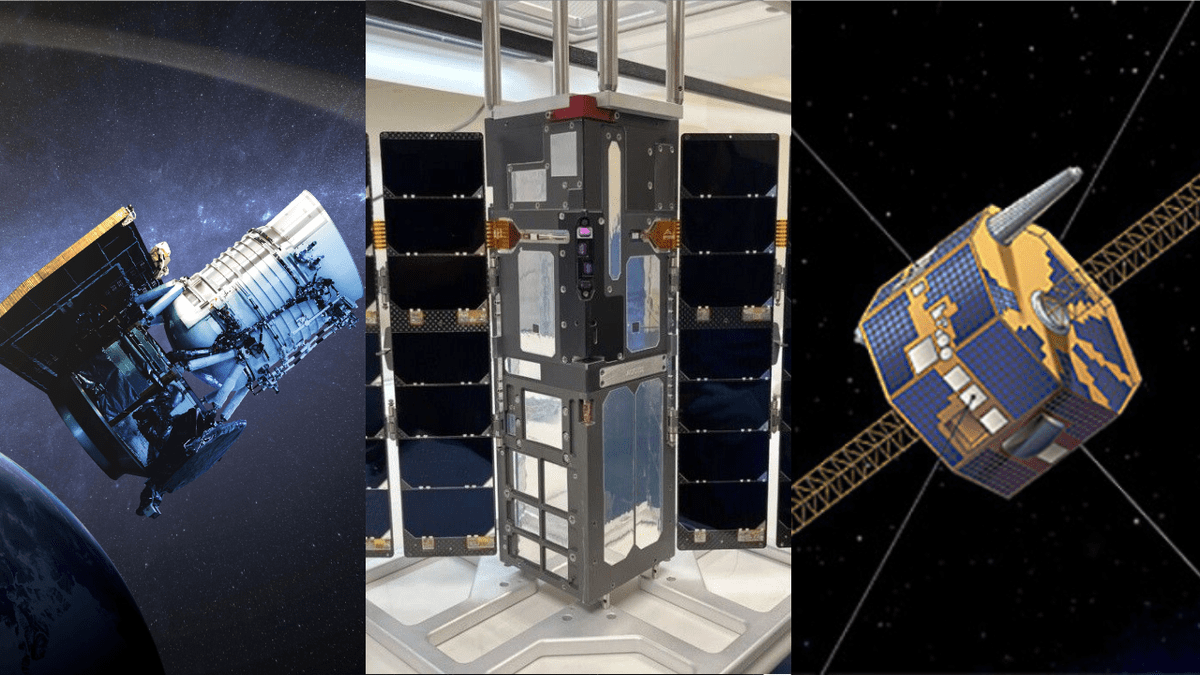

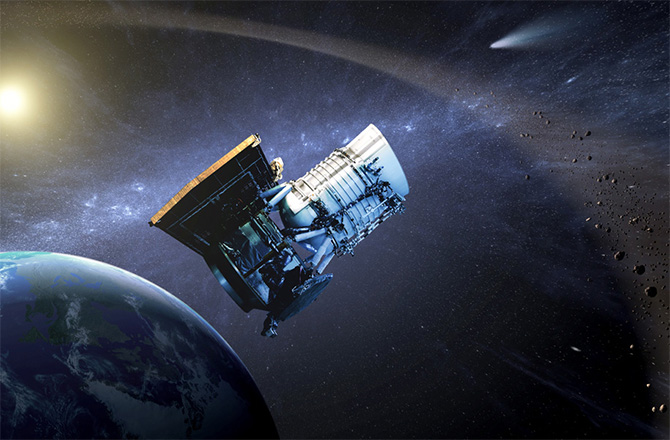

Occasionally, spacecraft are unexpectedly revived, like NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE). Launched in 2009, WISE was tasked with surveying the sky in infrared light but depended on coolant to maintain its instruments. Following coolant depletion in September 2010, NASA opted to stretch WISE’s mission in a new capacity as NEOWISE, dedicated to searching for near-Earth objects visible at warmer wavelengths that didn’t require coolant. NEOWISE was ultimately decommissioned in February 2011.

The Chelyabinsk meteor explosion in February 2013 prompted NASA to reactivate NEOWISE in September 2013. This led to a successful 11-year mission focusing primarily on hunting asteroids and comets, including the spectacular 2020 comet C/2020 F3 NEOWISE.

NEOWISE finally concluded its operations in August 2024, ultimately burning up upon reentering Earth’s atmosphere on November 1, 2024.

The ISEE-3 Narrative

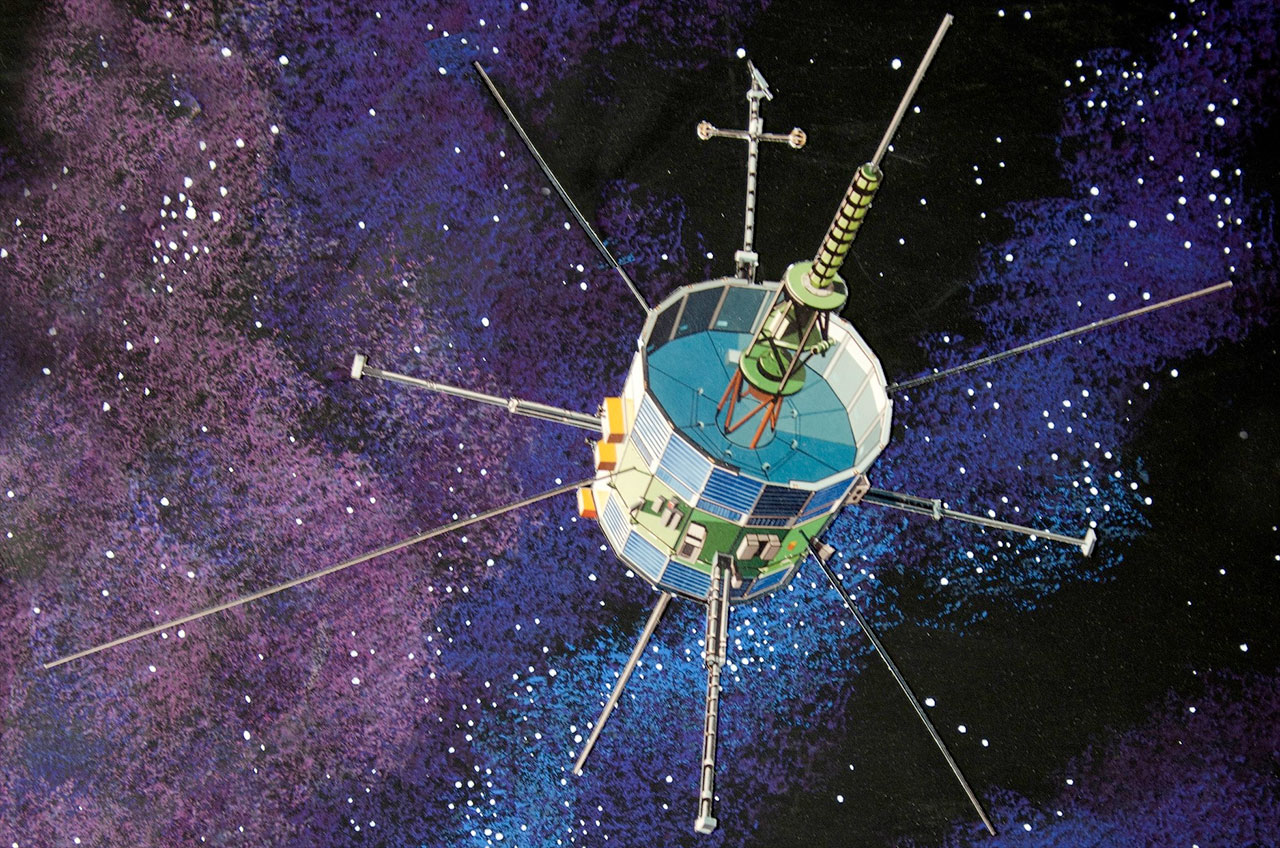

However, not all revivals yield successful results, as exemplified by NASA’s ISEE-3 mission, also known as the International Cometary Explorer, launched in 1978. This craft made history as the first to approach a comet, passing close to comet Giacobini-Zinner in September 1985. After a stint of operation until 1997, it was intermittently checked on in 1999 and 2008, but then left dormant.

In 2014, a passionate group of space enthusiasts received NASA’s approval to reactivate ISEE-3. On May 29, they established two-way communication, managing to ignite a few thrusters before running into complications as the nitrogen pressure in the onboard fuel tanks began to drop. The last confirmed contact occurred on September 16, 2014.

Though the initiative was well-intentioned — had it succeeded, it could have paved the way for reviving other dormant satellites — the reality of spacecraft reanimation is far more complicated. Just as CIRBE and IMAGE illustrated, sometimes a craft appears to lay at rest, only to surprise us with an unexpected comeback.