Neanderthals might have been on a path to extinction much sooner than previously believed, according to recent research findings.

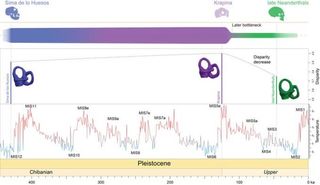

Published online on February 20 in the journal Nature Communications, the study reveals that approximately 110,000 years ago, Neanderthals faced a “population bottleneck,” leading to a severe decline in their genetic diversity.

A population bottleneck is characterized by a sudden drop in genetic variation within a species. Such occurrences can be triggered by various factors, including changes in climate, excessive hunting, or disease. The aftermath of a bottleneck often leads to a weakened population on the brink of extinction.

Researchers pinpointed the bottleneck by studying variations in the inner ear structures of Neanderthals over time.

Upon examining the inner ears of Neanderthal skulls, they found a noticeable decline in variations in these bones during the onset of the Late Pleistocene, indicating a critical transformation in the Neanderthal anatomy.

Typically, ancient DNA comparisons help researchers identify when population bottlenecks occurred. However, in this study, the team utilized the diminishing variations in the Neanderthals’ ear bones as a substitute measure. They concentrated on the semicircular canals—bony structures in the inner ear fully developed at birth. These canals, filled with fluid during an individual’s lifetime, play a vital role in balance and detecting head movements, such as nodding or shaking. Since variations in semicircular canals are evolutionarily neutral (not impacting survival), monitoring subtle changes over time can provide insights into the size and diversity of historical populations.

Utilizing CT scans, the team examined the semicircular canals of 30 Neanderthal specimens from three distinct periods: 13 from Sima de los Huesos in Spain, dated to 430,000 years ago; 10 from Krapina in Croatia, dating back to 120,000 years; and seven late Neanderthals from France, Belgium, and Israel, aged between 64,000 and 40,000 years.

This investigation indicated that the later group of Neanderthals exhibited a markedly lower variation in their inner ear bones compared to earlier populations, leading to the conclusion that a genetic bottleneck occurred more recently than 120,000 years ago.

“By incorporating fossils from a diverse range of geographical and temporal contexts, we achieved a clearer understanding of Neanderthal development,” stated study co-author Mercedes Conde-Valverde, a biological anthropologist at the University of Alcalá in Spain, in a statement. The significant reduction in diversity observed between early and late Neanderthals “is particularly notable and provides compelling evidence of a bottleneck event,” she commented.

These discoveries align with prior findings regarding Neanderthals, including indications of population turnover that adversely affected the populations of European Neanderthals. However, whether a similar trend was observed in southwestern Asian Neanderthals, such as those from Shanidar in Iraqi Kurdistan, remains uncertain, as their skulls have not been included in this analysis.

Test Your Knowledge: How Much Do You Know About Neanderthals?