A recent small-scale trial suggests that digoxin, an age-old medication traditionally used for heart conditions, may hinder the spread of cancer by breaking down clusters of cancer cells.

Experts emphasize that this research is still in its preliminary stages, so it may take time before we can determine its effectiveness in treating various cancers, including breast cancer.

Breast cancer stands as one of the top causes of cancer-related deaths among women in the U.S., primarily due to its propensity to metastasize, or spread, from the breast to other organs. This migration of cancer cells can infiltrate crucial organs, such as the brain and lungs, complicating treatment options. While conventional cancer therapies concentrate on eradicating tumor cells, they do not specifically target metastatic activity.

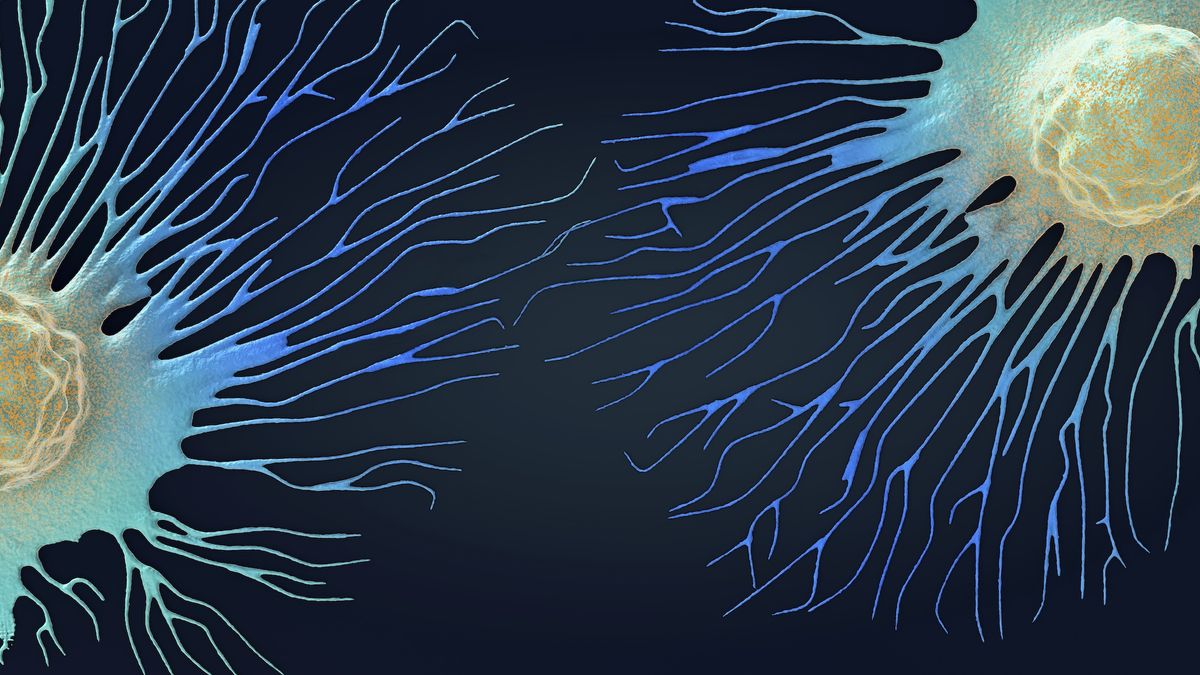

The process of metastasis heavily relies on circulating tumor cells—cancer cells that break away from primary tumors and enter the bloodstream. These tumor cells are significantly more likely to establish new tumors elsewhere in the body when they group together, as opposed to when they disperse independently.

Recent investigations in Switzerland have uncovered existing medications that may effectively separate these cell clusters. Experiments conducted on mice revealed that specific drugs were able to slow the progression of breast cancer, indicating a novel strategy for limiting metastasis. Known as Na+/K+ ATPase inhibitors, these medications include digoxin and alter the movement of charged particles across cell membranes.

Building on prior findings, scientists have carried out a clinical study to evaluate whether digoxin can diminish circulating tumor cell clusters in women diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer. Their preliminary results, released on January 24 in the journal Nature Medicine, indicate that digoxin might eventually support other therapies aimed at treating primary tumors, which are cancers that have not yet metastasized.

First Human Study of Digoxin in Cancer

Digoxin, derived from the foxglove plant (Digitalis lanata), has been utilized since 1930 for treating heart failure and atrial fibrillation. The drug functions by inhibiting structures in heart cells known as sodium-potassium pumps, which regulate sodium and potassium levels within cells. By blocking these pumps, digoxin strengthens heart contractions and decreases the heart rate.

Current scientific inquiries suggest that this effect of digoxin could be harnessed for cancer therapy.

By obstructing sodium-potassium pumps in cancer cells, digoxin leads those cells to absorb higher levels of calcium. Pioneering studies have indicated that increased calcium levels can interfere with the formation of tight junctions and desmosomes— structures that help cells adhere to one another. This implies that digoxin may reduce the cohesiveness of cancer cells, encouraging them to disperse.

The research team observed these effects in animal models. To ascertain whether digoxin could similarly impact tumor-cell clusters in human subjects, they enlisted nine women diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer, all of whom were found to have at least one circulating tumor cell cluster during the screening process.

Throughout the study, the participants consumed digoxin daily for a week. Blood samples were collected at various intervals to monitor the circulating tumor cells, including before treatment, two hours after the first dose, and again three and seven days later.

The analysis showed a reduction in the size of cancer-cell clusters, revealing an average decrease of 2.2 cells per cluster following treatment. Before intervention, the average size of the clusters was four cells. Importantly, no severe adverse effects were noted during the trial.

Questions to Address

While the trial findings are promising, they do come with certain constraints.

Although the reduction in tumor-cell clusters was statistically significant, the overall efficacy of the drug appears to be limited. Dr. Daniel Smit and Dr. Klaus Pantel, both affiliated with the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf in Germany, noted in a commentary regarding the recent study.

Theoretically, reducing the number of circulating clusters could lower the risk of further cancer spread; however, it may not stop existing secondary tumors from developing, suggesting that the drug’s utility may be relevant only at specific cancer progression stages.

Furthermore, Smit and Pantel pointed out that digoxin did not prevent circulating tumor cells from combining with healthy cells, another mechanism that facilitates cancer spread. Previous clinical trials conducted by different teams have indicated that while separating cell clusters might decelerate metastasis, tumor cells that migrate alone also correlate with adverse outcomes.

Importantly, both Smit and Pantel emphasized the varied clinical responses seen in metastatic breast cancer patients. Thus, while findings based on a cohort of nine individuals are insightful, they are still preliminary rather than conclusive.

Despite these limitations, the trial suggests that digoxin, alongside similar medications, could play a role in cancer therapy. The research team is now looking to develop new molecules based on digoxin that might be more effective at breaking apart circulating clusters and is also exploring its application in other cancer types.

This article is intended for informational purposes only and should not be construed as medical advice.