Recent findings suggest that certain species of megafauna may have existed far longer than previously believed.

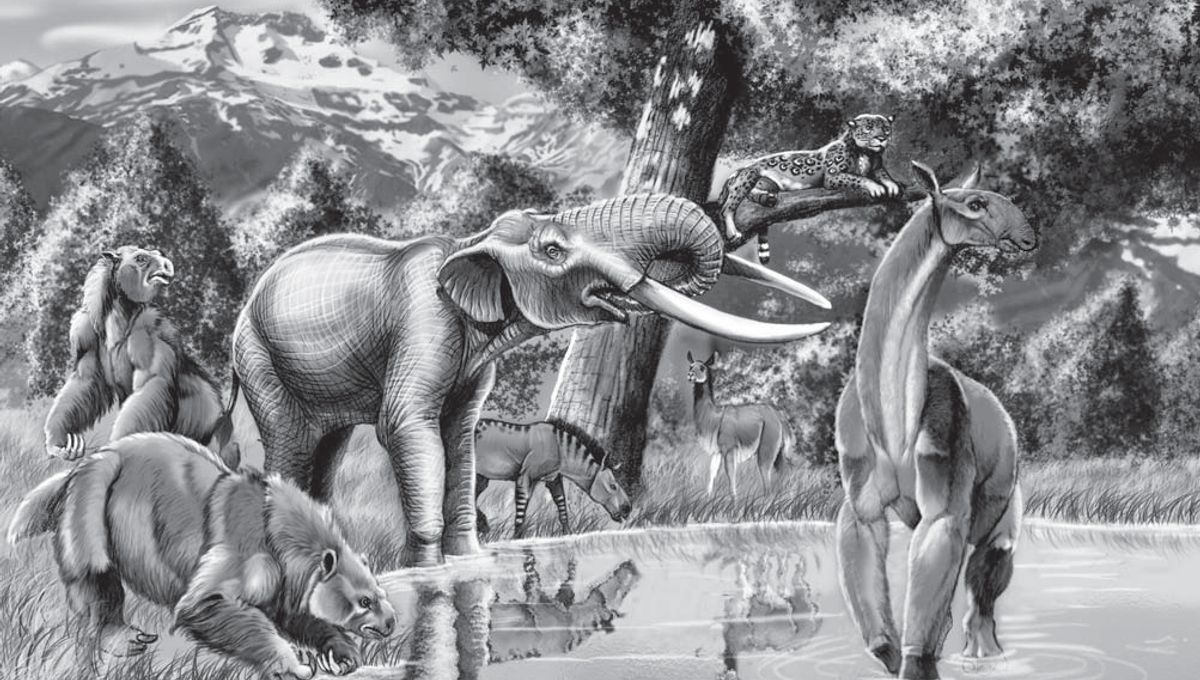

Historically, it has been widely accepted that mammalian megafauna—large mammals that once roamed the Earth, such as mammoths, colossal sloths, and sabertoothed cats—went extinct at the onset of the Holocene era. This geological period began approximately 11,700 years ago, marking the conclusion of the last significant glacial period.

However, recent research has uncovered fossil evidence that contradicts this longstanding belief. Notably, the discovery that woolly mammoths survived until about 4,000 years ago has generated skepticism regarding the traditional narrative. Furthermore, researchers have identified other megafauna remains, such as giant sloths and camel-like creatures, that thrived in South America until around 3,500 years ago.

This new evidence invites a reevaluation of the causes behind the recent extinction of large animals on the planet, indicating that it was not a uniform event.

The research, led by geologist Fábio Henrique Cortes Faria from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, involved carbon dating tooth fragments from various megafauna species found at two fossil sites in Brazil, including one in Itapipoca and another in the Rio Miranda valley. Among the eight specimens dated, two teeth—one from an extinct American llama species named Palaeolama major and the other from a camel-like animal resembling a tapir called Xenorhinotherium bahiense—were determined to be significantly younger than previously thought.

The authors state, “The ages obtained confirm that the latest instances of megafauna in Brazil align with the middle to late Holocene.”

If these species coexisted in Brazil during that period, it suggests they lived alongside humans, who likely arrived in South America between 20,000 and 17,000 years ago. This implies a prolonged period of coexistence, calling into question established beliefs about their extinction causes.

One predominant theory, known as the Overkill and Blitzkrieg hypotheses, suggested that South America’s megafauna faced significant threats from human hunting and potential habitat alterations; however, the accumulating evidence challenges this perspective.

The analyzed data, in conjunction with archaeological findings, indicate that the Overkill and Blitzkrieg theories may not adequately explain the extinction of South American megafauna.

It appears that the extinction process could have been gradual and did not occur uniformly across different regions. It is possible that the Brazilian area served as a refuge for certain megafauna species, allowing them to survive longer than others.

“This study illustrates that the well-known Pleistocene-Holocene extinction was a prolonged decline in the diversity of Pleistocene mammals,” stated researcher Ismar de Souza Carvalho to New Scientist.

The findings of this compelling study are published in the Journal of South American Earth Sciences.