Health reporter

Moorfields Hospital

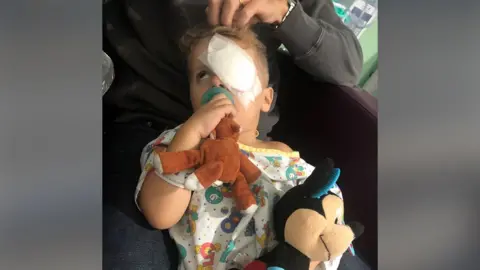

A groundbreaking gene therapy trial conducted at Moorfields Eye Hospital in London has demonstrated remarkable results, benefiting four toddlers diagnosed with severe childhood blindness. According to medical professionals, the therapy has provided these children with “transformative improvements” in their vision.

These children are affected by a rare genetic disorder that leads to rapid vision loss from infancy.

Prior to receiving therapy, they were classified as legally blind, only able to distinguish between light and dark. Following treatment, parents reported significant advancements, with some children now engaging in drawing and writing activities.

The initial findings of this study, published in the Lancet medical journal, call for further investigation to validate the outcomes.

The NHS has provided gene therapy for another form of genetic blindness since 2020.

This innovative approach enhances previous methods by introducing healthy gene copies into the child’s eye early in life to manage this severe condition.

Moorfields Hospital

At just two years old, Jace from Connecticut, USA, received gene therapy in London. His parents observed irregularities with his vision early on.

“By the time he was eight weeks old, when babies typically begin to focus and smile at you, Jace wasn’t responding,” shared his mother, DJ.

Concerned, she tirelessly sought answers for 10 months.

After numerous doctor visits and tests, the family learned that Jace had a very rare condition caused by a mutation in a gene known as AIPL1, for which no known treatment existed.

“It was shocking,” expressed Jace’s father, Brendan, regarding the diagnosis of their first child.

“You never expect this to happen to you, but it was a relief to finally have clarity… it gave us a direction moving forward.”

The family fortuitously discovered an experimental trial in London while attending a conference related to the eye condition.

According to his mother, Jace’s surgery was swift and “relatively straightforward”. He had four small scars where healthy gene copies were injected into the retina through minimally invasive techniques.

These healthy genes were delivered via a harmless virus that penetrates retinal cells and replaces the faulty gene, initiating a repair process to enhance cell functionality and longevity.

In the month following the treatment, Brendan noted Jace squinting for the first time when light flooded into their home.

“His progress has been quite remarkable,” he stated.

“Before the operation, if an object was held in front of him, he wouldn’t track it at all. Now, he’s reaching for items and playing with toys, engaging with the world in ways he couldn’t before.”

Though this may not be the only treatment Jace requires, his parents emphasize that the improvements have greatly enhanced his understanding of his surroundings.

“It’s hard to convey just how life-altering a little vision can be,” Brendan remarked.

Limited Alternatives

Moorfields Hospital

Professor James Bainbridge, a retinal surgeon at Moorfields Eye Hospital and one of the trial leaders, highlighted that enhancing children’s sight at such an early stage could significantly impact their overall development and social interactions.

“Visual impairment in early childhood can severely hinder development,” he noted.

“Administering this genetic treatment during infancy has the potential to change the trajectories of the most profoundly affected children’s lives,” he stated.

The four children involved in the trial hail from the United States, Turkey, and Tunisia, all suffering from a severe form of Leber Congenital Amaurosis. This genetic disorder causes the light-sensitive cells in the retina to malfunction and deteriorate quickly.

Researchers from University College London pioneered this groundbreaking technique that involves infusing healthy gene copies into the back of the eye.

Unlike conventional clinical trials, families received this experimental treatment under a special compassionate-use license when standard options were unavailable.

Each child underwent treatment in one eye, a precaution to monitor for possible adverse reactions.

The children, aged between one to three, had their vision assessed regularly over the following four years using varied methods, including navigating corridors and recognizing doors.

Given their young age, some found standard eye assessments challenging.

‘Impressive Outcomes’

Moorfields’ doctors state that the results from their evaluations, along with parental feedback, provide compelling evidence that all four children benefited from the therapy and experienced more vision than anticipated given the natural progression of their condition.

In contrast, the vision in their untreated eyes continued to decline, as expected.

Professor Michel Michaelides, a consultant eye surgeon at the UCL Institute of Ophthalmology, remarked, “The results concerning these children are remarkably encouraging and demonstrate the potential of gene therapy to profoundly improve lives.”

The research team plans to conduct ongoing assessments of the children to evaluate the durability of the results.

Current outcomes inspire hope that early intervention in other genetic eye disorders may yield significant advantages and potentially alter children’s lives for the better.