Utilizing advanced laser technology, researchers have uncovered a sacred roadway that dates back 1,000 years in proximity to Chaco Canyon, located in New Mexico. This path is believed to have been a part of an Indigenous ritual landscape, connecting natural springs and aligning with the sunrise during the winter solstice, according to new findings published in a recent study.

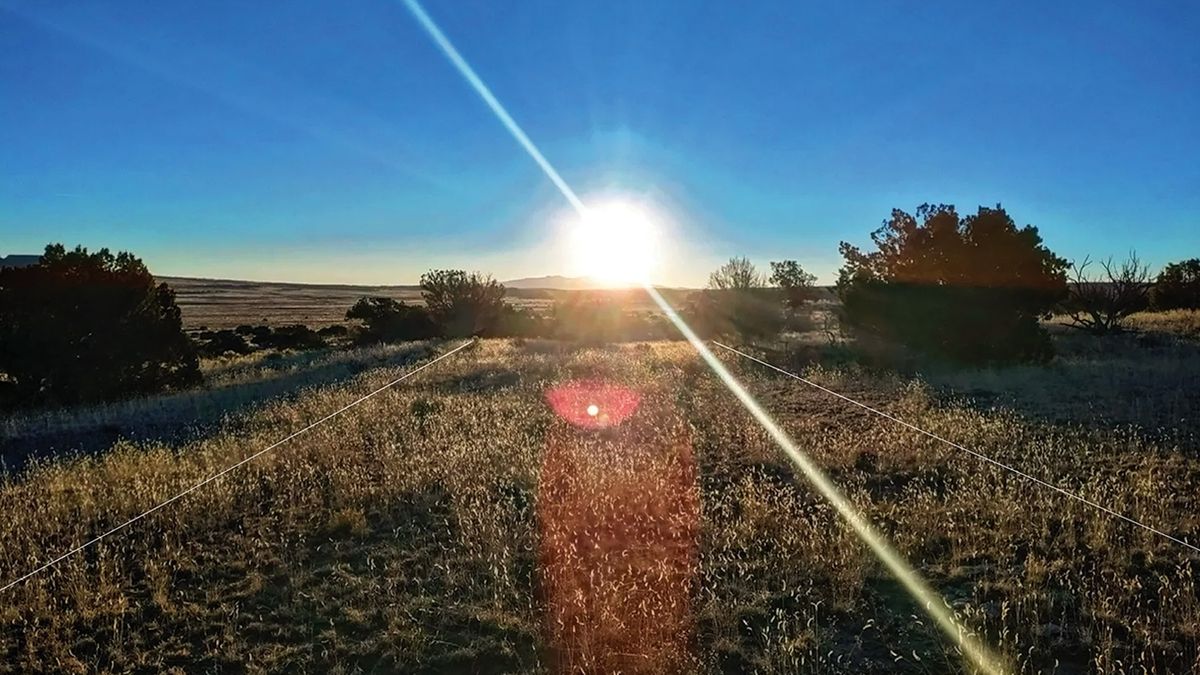

Previous assumptions suggested that the thoroughfare at the Gasco site may have connected Indigenous communities in the surroundings. However, the latest research reveals that this sacred road is significantly longer than initially estimated and is accompanied by another previously unknown road that runs nearly parallel to it. Notably, both roads line up with the winter solstice sunrise over Mount Taylor, which is considered a revered site among Indigenous cultures today, as detailed by the researchers in their study.

Located roughly 50 miles (80 kilometers) south of Chaco Canyon and west of Albuquerque, the discoveries at Gasco indicate that these Indigenous paths were not just for transportation but were essential to their cosmological framework, the researchers highlighted.

“One of the most thrilling outcomes of our research on Chacoan roads is that they are prompting us to reevaluate the concept of what a road signifies,” stated Robert Weiner, an archaeologist from Dartmouth College, in an interview with Live Science.

Using publicly available lidar maps—which utilize laser pulses to map landscapes obscured by vegetation—researchers mapped the Gasco site road, discovering it spans nearly 4 miles (6 km) in length, considerably more than the few hundred feet previously known. Their findings were further substantiated by subsequent fieldwork conducted in 2021 and 2022, as documented in the study published on January 24 in the journal Antiquity.

Additionally, researchers identified a second road that lies approximately 115 feet (35 m) to the south of the first, plus an extra “herradura”—a horseshoe-shaped wall of rocks that may have served as a roadside shrine.

Related: The First Americans Were Not Who We Thought They Were

Intriguing Indigenous Culture

The Chaco culture flourished in the American Southwest from around A.D. 850 to 1250, centuries before European contact. According to Weiner, this culture may have initially arisen as a religious movement, although much remains unknown about their beliefs.

Renowned for their astonishing, now-abandoned pueblo structures at Chaco Canyon and beyond, it is increasingly believed that severe droughts and other crises contributed to the decline of the Chacoan civilization.

Several Indigenous groups that descend from the Chacoans include the Hopi and Zuni peoples, alongside the Diné, often known as the Navajo, who also inhabit the region.

Understanding Chacoan Roads

The intriguing formation of two nearly-parallel roads has appeared at other Chacoan sites, suggesting a dualistic representation within their cosmological beliefs, as noted by Weiner.

These significant roads, which were cut into sandstone bedrock and measure about 30 feet (9 meters) wide, exceed the dimensions necessary for a culture lacking wheeled vehicles or pack animals. The routes feature stairways and ramps, with sections lined by sandstone and earth from excavation activities.

Weiner stated that the adjacent herraduras—one previously identified along the northern road and the other newly discovered alongside the southern road—likely functioned as focal points for ritual events during sacred processions. This premise is bolstered by finding ceramic shards and shaped stones that may have served as offerings. It is posited that one road, along with its adjacent herradura, was utilized in winter, while the other set was more prominent in summer.

While practical uses, such as transporting timber, might have been part of their functionality, it appears the roads primarily served spiritual purposes within Chacoan traditions.

According to Stephen Lekson, an anthropologist at the University of Colorado Boulder and an expert on Chaco culture, who wasn’t directly involved in the recent research, the vast prehistoric road system constructed by the Chacoans spans an area approximately the size of Ohio.

“Chaco’s unique geography is preserved through its roadways, as well as much of its cosmological significance,” he explained, before pointing out how archaeologically rich even a single segment of this network can be.

However, Lekson cautioned that numerous Chacoan sites are now endangered by energy-related projects on public lands—initiatives that have the potential to “irreparably damage this vital chapter of Pueblo and Navajo heritage,” he warned.