CNN —

A measles outbreak in West Texas has resulted in numerous infections, highlighting the importance of recognizing the symptoms of this disease, particularly in young children.

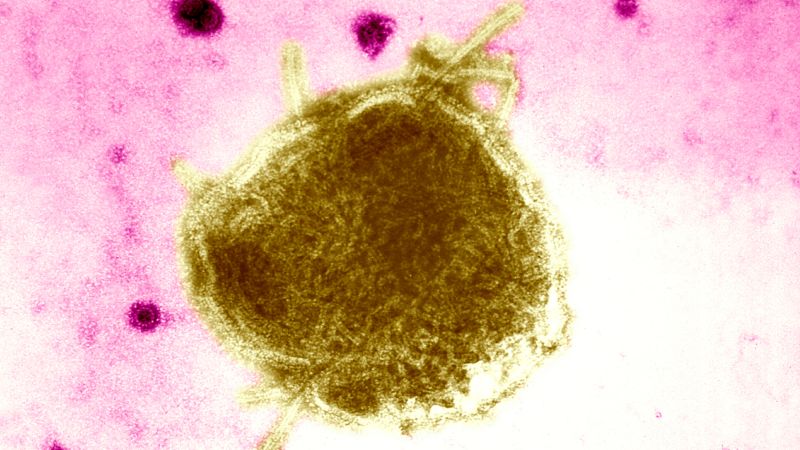

Measles is among the most contagious infectious diseases worldwide and can lead to severe complications, including blindness, pneumonia, and encephalitis, which is brain swelling. Tragically, it can be fatal, especially for children under the age of five.

Dr. Melissa Stockwell, a pediatric professor at Columbia University’s Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, stated, “Around 20% of unvaccinated individuals in the U.S. with measles require hospitalization, and about 5% of children with the virus develop pneumonia, the leading cause of measles-related deaths in young children.”

In total, it is estimated that as many as three out of every 1,000 children infected with measles could succumb to respiratory and neurological complications.

Stockwell encourages families with concerns to connect with their child’s healthcare provider to discuss the facts about measles and the importance of vaccination.

Vaccination remains the most effective means of preventing measles. However, a recent report indicated that a record number of kindergarteners in the U.S. received exemptions from mandatory vaccinations last school year, resulting in over 125,000 incoming students lacking coverage for at least one required vaccine, according to CDC data released in October.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services aims for at least 95% of kindergarten children to receive two doses of the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine, a target essential for preventing outbreaks of this highly contagious illness.

Unfortunately, the U.S. has failed to achieve this target for four consecutive years.

Currently, the ongoing outbreak in West Texas is predominantly affecting Gaines County, where MMR vaccine coverage is alarmingly low, with nearly 20% of incoming kindergarten students during the 2023-24 school year unvaccinated.

Early-stage measles can mimic symptoms of other respiratory conditions, such as the flu or a common cold.

“Initially, differentiating measles from other respiratory illnesses can be challenging. The combination of three symptoms—cough, conjunctivitis (red eyes), and coryza (stuffy nose)—is particularly telling,” advised Dr. Glenn Fennelly, a pediatric infectious disease specialist and assistant vice president for global health at Texas Tech Health El Paso.

“If all three symptoms are present, it warrants concern,” he added.

Other significant symptoms of measles include a high fever, which can exceed 104 degrees Fahrenheit, a distinctive red, blotchy rash, and Koplik spots—small white spots that can appear in the mouth two to three days after initial symptoms.

“While early symptoms of measles may overlap with other respiratory viruses like a runny nose, cough, and fever, the characteristic rash usually appears three to five days after other symptoms begin,” Stockwell noted.

If an individual develops these symptoms, it’s crucial to consult their physician or healthcare team before visiting a clinic, urgent care, or emergency department, according to Fennelly.

“Measles is highly infectious. It’s advisable to inform the healthcare facility ahead of time so they can prepare,” he explained, as immediate isolation is warranted.

Notifying the healthcare provider in advance allows for necessary preparations and advice to minimize the risk of measles transmission in crowded waiting areas.

The measles virus spreads through respiratory droplets from coughing, sneezing, and even by inhaling air contaminated by an infected person. The virus can linger in the environment for up to two hours, even after the individual has left the area.

It’s estimated that one measles-infected person can transmit the virus to 9 out of 10 unvaccinated close contacts. The highly contagious nature of measles is compounded by the fact that an infected individual can spread the virus even before exhibiting symptoms—specifically from four days prior to the onset of the rash to four days after.

“The optimal way to protect children is through timely immunization, beginning at 12 months of age, with a second dose recommended between 4 to 6 years,” Fennelly stated.

The measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine has proven to be both safe and effective. One dose offers a 93% efficacy rate against measles, while two doses boost this protection to 97%.

Health officials recommend that children receive two doses of the MMR vaccine: the first between 12 and 15 months, with the second dose around age 4, before commencing school. These two immunizations typically confer lifelong protection against measles.

Although the vaccine is not foolproof, increasing measles exposure raises the risk of infection, even among vaccinated individuals. Nonetheless, symptoms are generally milder in vaccinated individuals, who are also less likely to transmit the virus to others.

If a person is exposed to measles, the CDC advises that receiving the MMR vaccine within 72 hours may offer some protection or mitigate the severity of the illness.

Adults and older children who missed their childhood vaccinations can still receive the vaccine. However, individuals born before 1957 are likely to have acquired natural immunity through past infections, according to the CDC.

For those who received the initial killed-virus measles vaccine administered between 1963 and 1968 or are unsure about their vaccination type, the CDC recommends at least one dose of the MMR vaccine.

Before the measles vaccination program began in 1963, the disease caused approximately 2.6 million deaths annually worldwide. In 2023, the World Health Organization estimated there were 107,500 measles-related fatalities, predominantly in countries with low vaccination rates.

In the U.S., there has been a recent decline in vaccination rates among some parents, largely fueled by misinformation, including the false belief that vaccines are linked to autism.

“Measles vaccines are proven to be safe and effective. There is no credible research establishing a connection to autism,” stressed Fennelly. “The safety of the measles vaccine is evident, supported by millions of children vaccinated without complications. What should truly concern parents is the disease itself, which can lead to serious consequences.”

While there is no specific antiviral treatment for measles, certain complications can be managed.

“Unfortunately, no definitive treatment exists for measles,” Stockwell noted in her email.

“Sometimes measles can lead to secondary infections, such as ear infections or pneumonia, which may require antibiotics,” she continued. “Additionally, vitamin A can be a crucial complementary therapy for measles that helps prevent severe illness and mitigate some adverse effects.”

Fennelly highlighted that measles is a “strongly immunosuppressive” virus, which weakens the immune system of those infected, making them more vulnerable to bacterial infections such as pneumonia, a leading cause of measles-related mortality.

“Children with measles may develop bacterial infections in their respiratory systems that necessitate antibiotic treatment,” he stated.

Furthermore, “any child requiring hospitalization will likely receive high-dose vitamin A,” he advised. “Vitamin A has demonstrated significant benefits during acute measles, potentially leading to a 50% reduction in mortality.”

Patients advised by their doctors to remain at home can manage symptoms with fever reducers, ample rest, and hydration.

“It’s vital to isolate the child during the contagious period while maintaining close communication with the pediatrician,” Fennelly emphasized. “If a child exhibits increased drowsiness or noticeable irritability, these are valid reasons to contact the pediatrician again.”