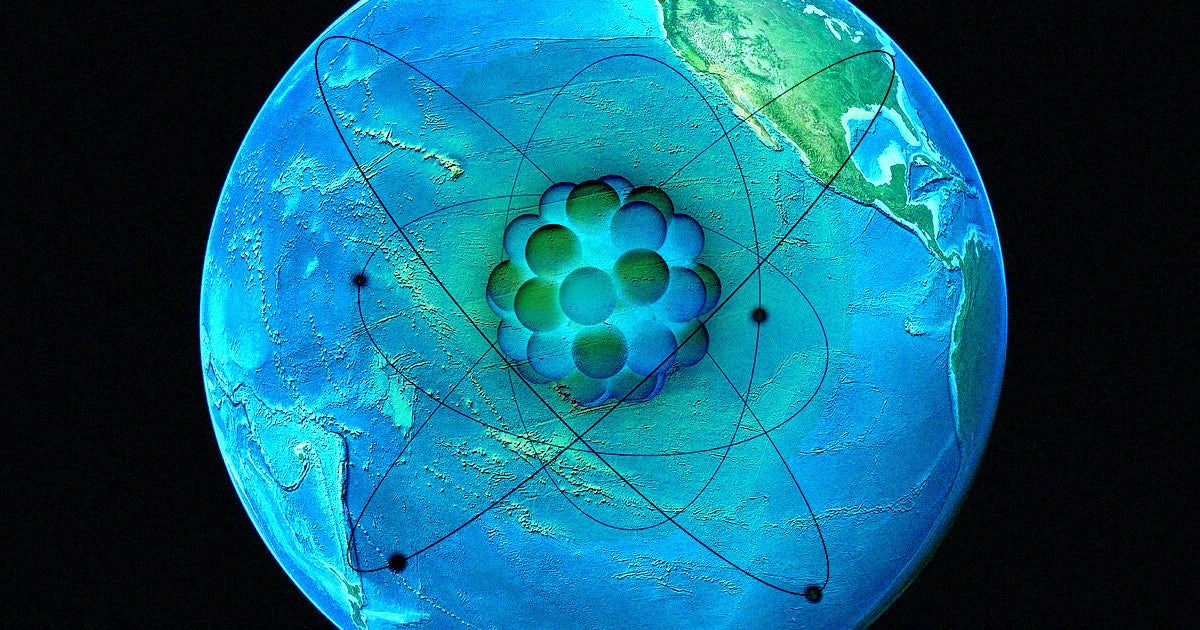

A recent study has unveiled an astonishing accumulation of the radioactive isotope beryllium-10, located deep beneath the Pacific Ocean’s surface.

In a research article published in the journal Nature Communications, an international team of scientists suggests that this “anomaly” may be linked to shifts in ocean currents or interactions of cosmic rays with Earth’s atmosphere, dating back approximately ten million years. Beryllium-10 is continually produced when oxygen and nitrogen atoms in the upper atmosphere interact with high-energy protons that travel through space at nearly the speed of light 1.

The researchers aim for this discovery to act as an “independent time marker for marine records,” which may help scientists better understand the evolution of Earth’s crust over millions of years and refine geological datasets.

Researchers frequently utilize radioactive isotopes for dating archaeological and geological materials. Radiocarbon dating, a common method, has its limitations, particularly when dating samples older than 50,000 years.

According to Dominik Koll, a physicist at Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf and coauthor of the study, “To analyze older samples, we need alternative isotopes like cosmogenic beryllium-10.”

This isotope has an impressive half-life of 1.4 million years and decays into boron, enabling scientists to trace back over ten million years of geological history.

In their study, Koll and his team investigated geological samples retrieved from the ocean floor, examining the ratios of boron isotopes through accelerator mass spectrometry.

The findings surprised the researchers.

“Around ten million years ago, we detected nearly double the amount of [boron-10 isotope] than we had expected,” Koll noted. “We had come across an unsuspected anomaly.”

The team can only hypothesize about the potential causes of the anomaly, which coincides with the period when gibbons and orangutans diverged, leading to early humans.

They propose that there may have been a “grand reorganization” of ocean currents, resulting in increased levels of beryllium-10 in the Pacific.

Interestingly, the anomaly could also stem from a significant celestial occurrence, such as a “near-Earth supernova” that might have intensified cosmic radiation around ten million years ago. A collision with an interstellar object could have made Earth’s atmosphere more susceptible to cosmic rays.

“Only further measurements can clarify whether the beryllium anomaly resulted from changes in ocean currents or whether it has astrophysical origins,” Koll stated. “This is why we intend to analyze additional samples in future studies and urge other research groups to do the same.”

If similar anomalies are identified in other oceans, it would suggest a global phenomenon, lending credence to the astrophysical hypothesis.

Learn more about cosmic rays: Scientist Warns That NASA’s Voyager Probes Are “Dodging Bullets Out There”